MetMatters guide to cloud spotting

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

Cloud spotter? Then you’re in the right place. In fact, the man who gave clouds their fancy Latin names was one of the original members of the Royal Meteorological Society. Luke Howard, pharmacist and amateur meteorologist was born 250 years ago, on 28 November 1772, and at the age of 30 he first proposed the cloud classification system we still use today. In December 1802, Howard presented the first draft of an essay titled "The Modifications of Clouds" to the Askesian Society. The Askesian Society was a small debating and self-improvement club joined by those with an interest in research and education. Howard wanted to emphasise the importance and usefulness of meteorology and visual observations of wind and clouds.

Before we get stuck into the names of clouds, let’s go over some basics. A cloud is a collection of tiny droplets of water or ice crystals. All air contains water but near the ground it is usually in the form of an invisible gas called water vapour. When warm air rises it expands and cools. Cold air can't hold as much water vapour as warm air so some of the vapour condenses onto tiny dust particles in the atmosphere and forms water droplets. When billions of droplets come together, they become a visible cloud. A good analogy to think of is the steam formed by a boiling kettle.

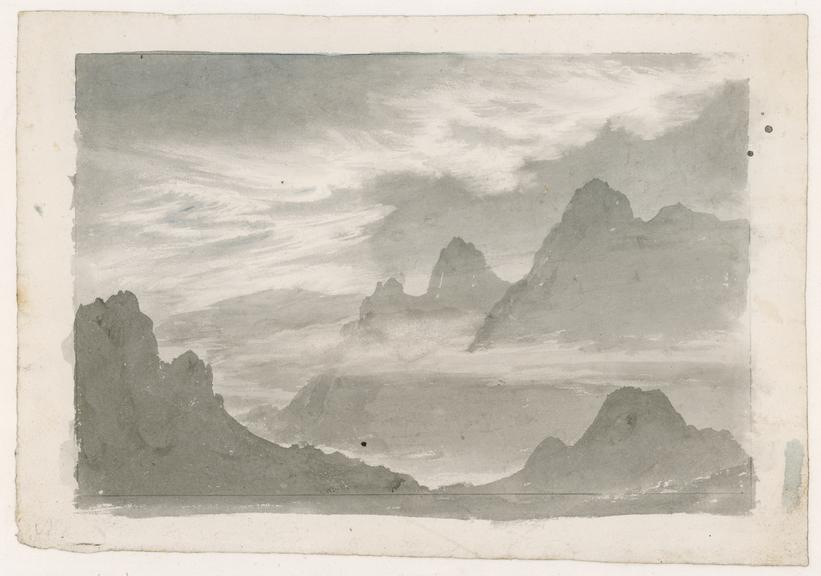

The range of ways in which clouds can be formed – for example from surface heating, air mass clashes or orographic forcing – and the variable nature of the atmosphere – results in an enormous variety of shapes, sizes and textures of clouds. And if you've ever spent quality time cloud gazing, then you'll know they also continually change.

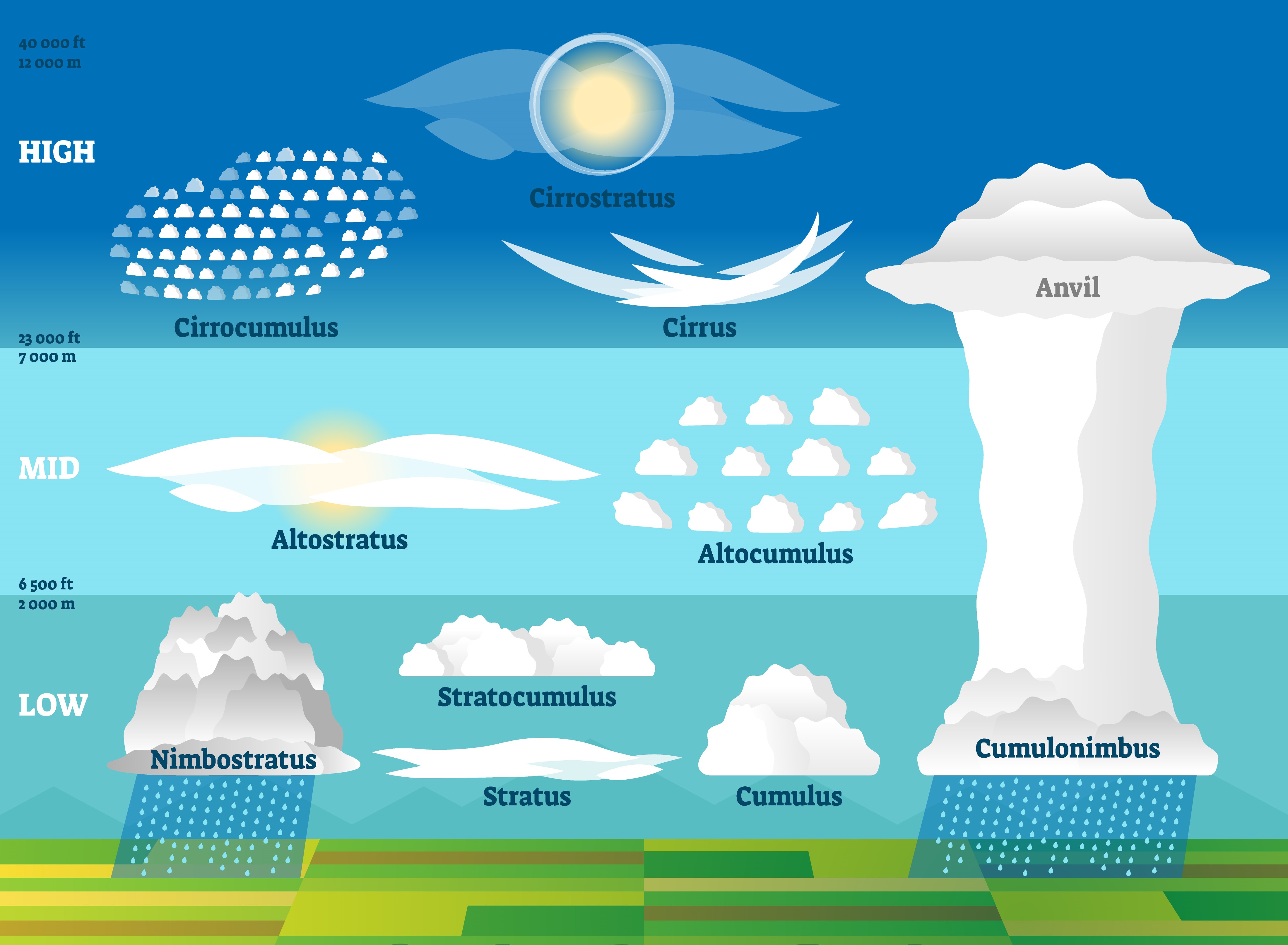

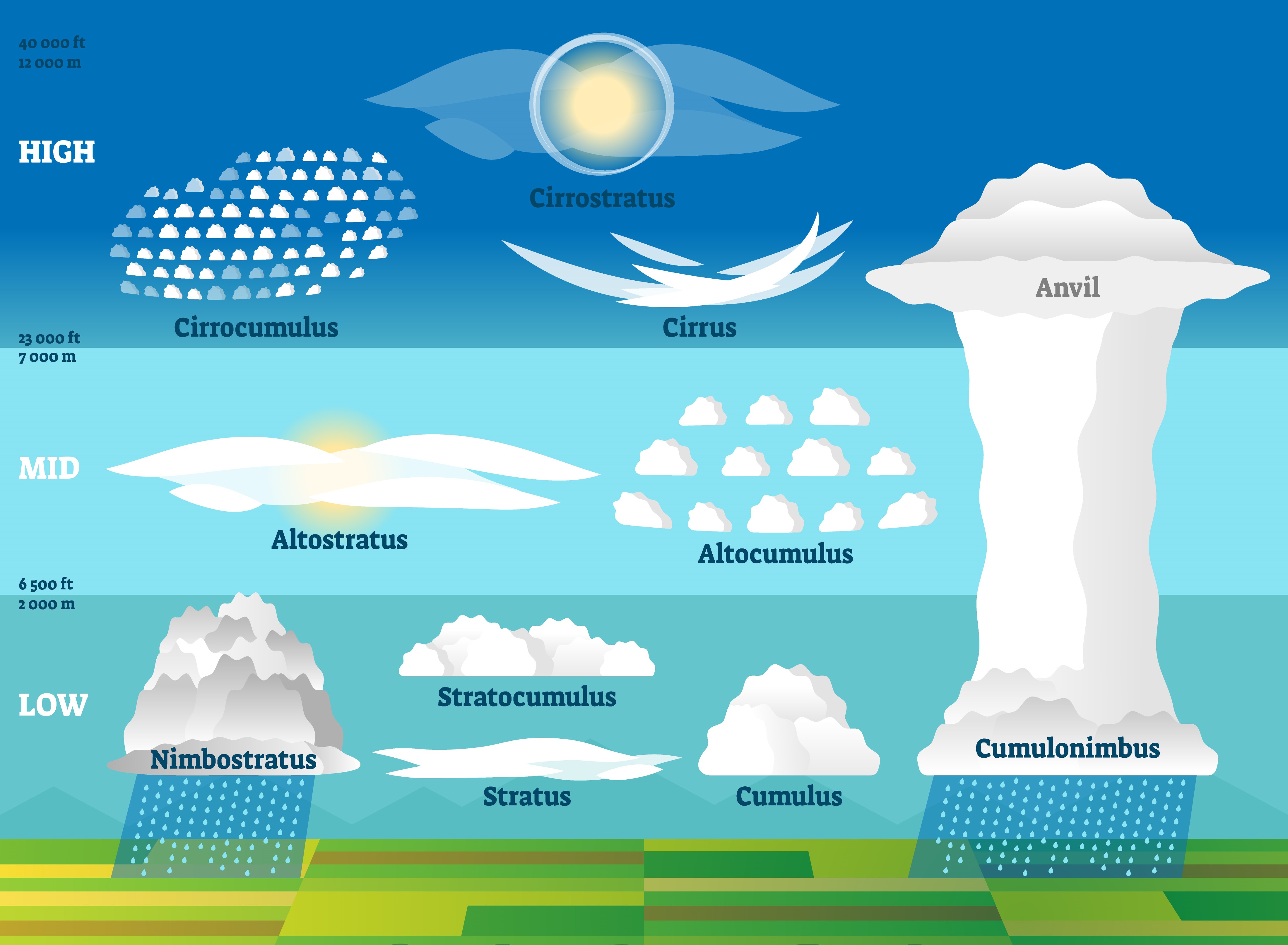

But Luke Howard identified characteristic forms that allowed him to group clouds into three main families based on their appearance. Rather than use the terms layered, puffy or fibrous, he gave them descriptive Latin names, which led to a more universal system. Add in attributes such as rain-bearing or height in the sky and we get the ten basic cloud groups. Here is our MetMatters cloud-spotters guide, which may even help you do some local weather forecasting.

Let’s start at the top with the high-level clouds that have a base at or above 20,000 ft over the UK.

Howard described cirrus clouds as "parallel, flexuous, or diverging fibres, extensible in any or all directions". They are the most common of the high clouds and so high up they’re composed of ice crystals instead of water droplets. These thin, wispy clouds get blown by high winds into long streaks, almost like tufts of hair, very apt given the word cirrus is Latin for lock or “curl” of hair. Cirrus clouds are usually white and predict fair to pleasant weather. Because they are so high up it can look like they aren’t moving, but they actually move the fastest of all the clouds and by watching their movement you can tell from which direction weather is approaching. Often cirrus clouds indicate a change in the weather will occur within 24 hours.

These are sheet-like clouds that often cover the entire sky spanning thousands of miles and they are thin enough that the sun or moon can be seen through them. Howard defined cirrostratus as "horizontal or slightly inclined masses, attenuated towards a part or the whole of their circumference, bent downward or undulated, separate, or in groups consisting of small clouds having these characters". They sometimes produce white or coloured rings, spots or arcs of light around the sun or moon known as halo phenomena. They usually come 12 to 24 hours before a rain or snowstorm.

These appear as small, rounded white puffs in long rows. The small ripples sometimes resemble the scales of a fish. They are relatively rare, tend to be seen in winter and indicate fair but cold weather. In tropical regions they may indicate an approaching hurricane. Howard described these as "small, well-defined roundish masses, in close horizontal arrangement".

Now we get a bit closer to earth with the medium-level clouds, which have bases between 6,500 and 20,000 ft over the UK.

These grey clouds are composed of ice crystals and water droplets and usually cover the entire sky. In thinner areas the sun may be dimly visible as a round disc. Altostratus often forms ahead of storms so are associated with approaching weather fronts.

Altocumulus are mostly made of water droplets and appear as rounded lumps, usually forming in groups. If you can't tell whether you've spotted altocumulus or cirrocumulus look for shading, cirrocumulus are white but altocumulus can be white or grey and the sides will be shaded. If you see altocumulus clouds on a warm, sticky morning get ready for some rumbles of thunder in the afternoon.

These are dark grey, featureless layers of cloud, thick enough to block out the sun and associated with continuously falling rain or snow. Nimbus is the Latin word for rain. Howard called this "the rain cloud"; unsurprisingly, nimbus is the Latin word for rain. He described it as "a horizontal sheet, above which the cirrus spreads, while the cumulus enters it laterally and from beneath". Although classed as a mid-level cloud, the base can lower to near the Earth's surface.

And finally, there are the low-level clouds, with a cloud base usually below 6,500 ft in the UK.

Howard classified stratus clouds as "a widely extended, continuous, horizontal sheet, increasing from below". These uniform, rather featureless grey clouds often cover the entire sky. Usually found around coasts and mountains, it's one of the lowest forming clouds. Light mist or drizzle often falls from these clouds and when stratus lowers all the way to the ground it's called fog.

Low, puffy and grey. Most of these clouds form in rows with blue sky visible between. Howard described it as "the cirrostratus blended with the cumulus, and either appearing intermixed with the heaps of the latter or super-adding a widespread structure to its base". Rain rarely occurs with stratocumulus; however, they can turn into nimbostratus.

Howard defined cumulus clouds as "convex or conical heaps, increasing upward from a horizontal base". These white, puffy clouds with tops like cauliflowers often form on sunny days and are known as fair-weather clouds. They typically appear late in the morning, grow and change, before dissipating into the evening. But they can grow upwards and become towering cumulus (cumulus congestus) and eventually develop into giant thunderstorm clouds known as...

The big baddy of the skies – it may well have a base in the low category, but it can grow all the way to the top of the troposphere. These thunderstorm clouds are associated with heavy rain, snow, hail, lightning and even tornadoes. The top of the cloud is formed of ice crystals that get blown into an anvil shape by high winds, indicating the direction in which the storm is moving.

On World Meteorological Day in 2017 (23rd March), the World Meteorological Organization released its new, online, digitised International Cloud Atlas, the global reference for observing and identifying clouds which contained several new cloud classifications.

About Luke Howard

Luke Howard was born in London on 28 November 1772, the first child of successful businessman Robert Howard and his wife, Elizabeth. He was educated at a Quaker school at Burford in Oxfordshire and was then apprenticed to a retail chemist in Stockport.

He became, like his father, a businessman, developing a firm that manufactured pharmaceutical chemicals. His real interest was, though, in meteorology, and he made several significant contributions to the subject besides his cloud classification.

He published The Climate of London (first edition 1818, second edition 1830), Seven lectures on meteorology (1837), A cycle of eighteen years in the seasons of Britain (1842) and Barometrographia (1847).

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 8 March 1821 and joined the British (now Royal) Meteorological Society on 7 May 1850, only a month after the society was founded. He died in London on 21 March 1864.

Want to know more?

This month we have a Special Issue of Weather to mark the 250th anniversary of Luke Howard's birth.

As well as a wonderful short video dedicated to the work of Luke Howard, the Science Museum has written a timely article about his pioneering role in climate studies.

Further resources

If you would like to learn more about cloud names and cloud classifications, please take a look at our additional resources:

- Buy the laminated, fold-out Key to Clouds from the Society shop

- Download the cut-out cloud wheel from the Royal Meteorological Society's education resource site, MetLink

- Test your cloud identification skills using our interactive cloud guide