Atlantic hurricanes, British weather, warmer waters and climate change

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

Did you know that the hurricanes and tropical storms that form during the Atlantic hurricane season can affect our weather in the UK and Ireland? We may not get “proper” hurricanes (our sea surface temperatures just aren’t high enough), but tropical cyclones do influence our weather — both directly and indirectly. Which is why it’s worth paying close attention to what’s happening on the other side of the pond.

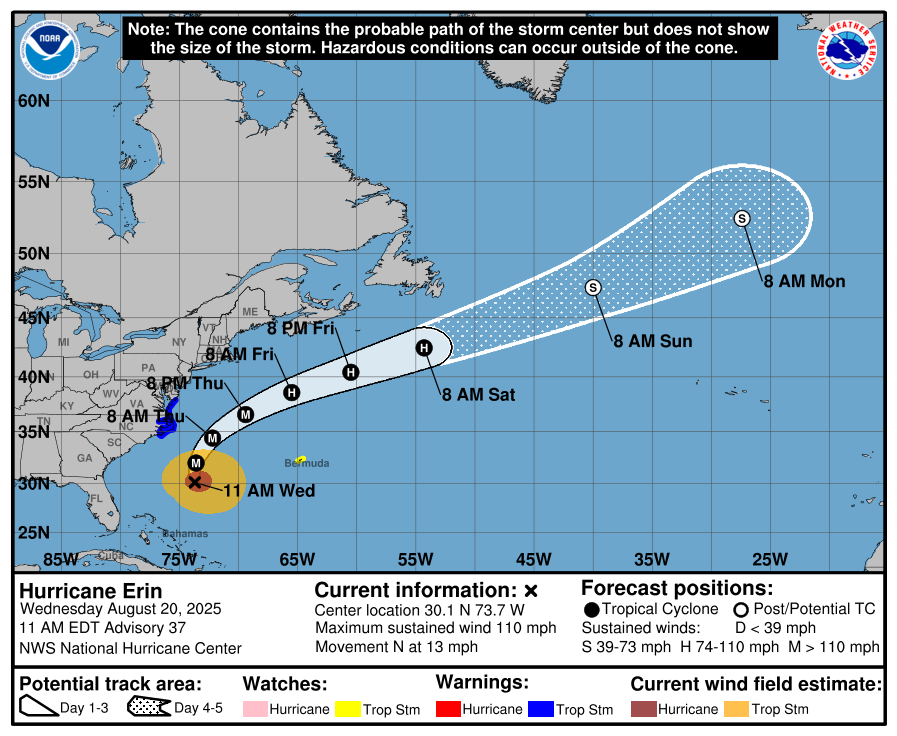

Take Hurricane Erin, the first hurricane (and the first major hurricane) of the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season. Erin reached Category 5 strength with peak winds of 160mph on 16 August after undergoing rapid intensification. Climate Central has released preliminary data showing that the rapid strengthening occurred as Erin passed over unusually warm ocean waters. And that climate change made the 1.1°C increase in ocean temperatures at least 90 times more likely.

Erin is forecast to track northeastwards away from the US and weaken as it heads towards the UK, losing all its tropical characteristics and effectively becoming an area of low pressure containing the remnants of the ex-hurricane. Nicely timed to bring unsettled weather for the last week of summer, something that often happens at this time of year as hurricane activity tends to ramp up from August, with a peak in activity from late August through September.

Even if we don’t get the remnants of the ex-hurricane directly heading our way, tropical storms can influence the behaviour of the jet stream, altering the position of highs and lows in our atmosphere and indirectly changing our weather.

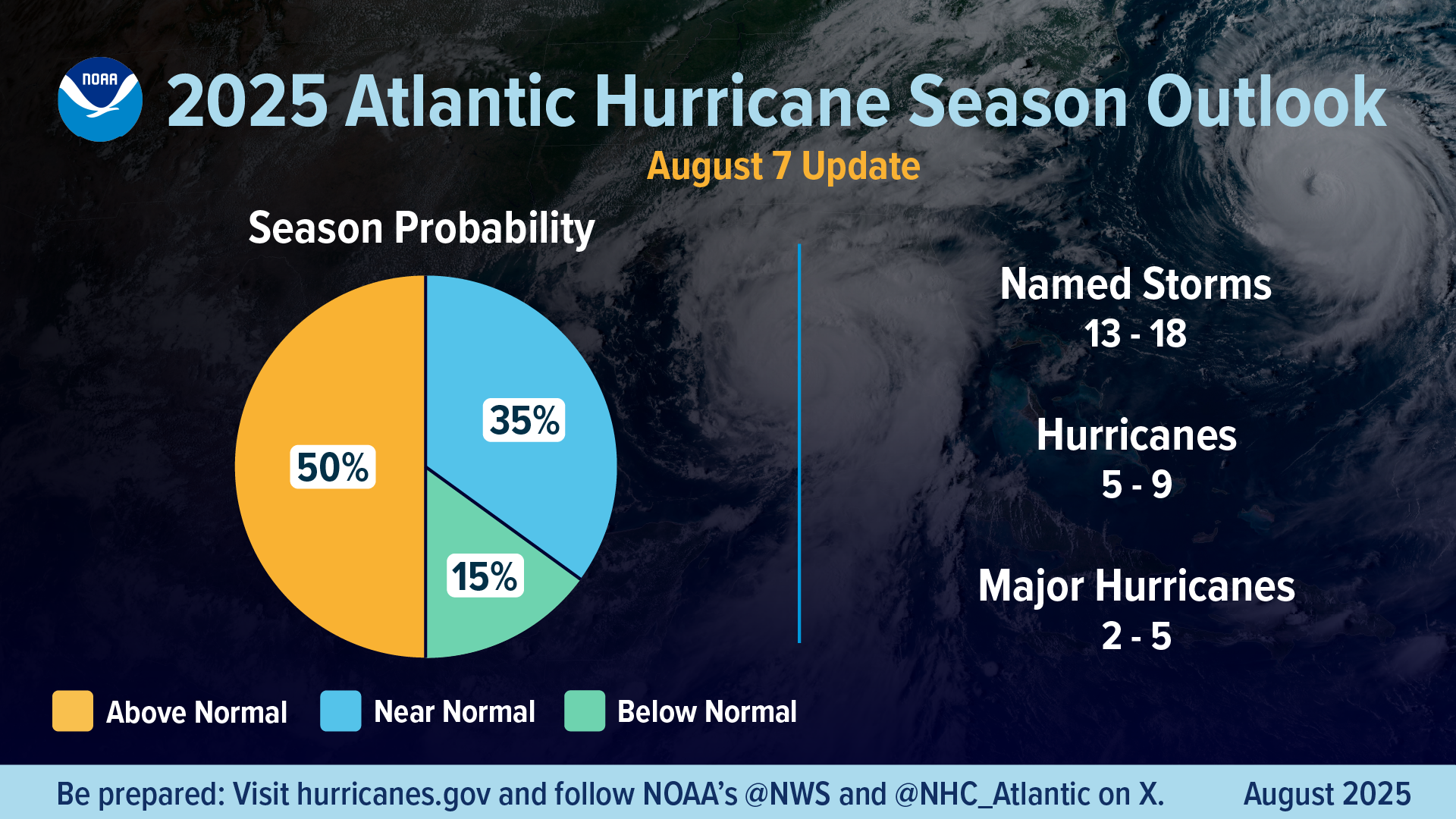

In May 2025, forecasters from NOAA’s National Weather Service predicted another above-normal hurricane season for the Atlantic basin. The August update confirmed that atmospheric and oceanic conditions continued to favour an above-normal season.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from 1 June to 30 November and covers the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricanes begin their lives as clusters of clouds and thunderstorms called disturbances. If certain key ingredients are in place — sea surface temperatures of at least 26.5 °C, along with low wind shear so the storm cloud can rise vertically — these disturbances can grow into tropical storms or hurricanes.

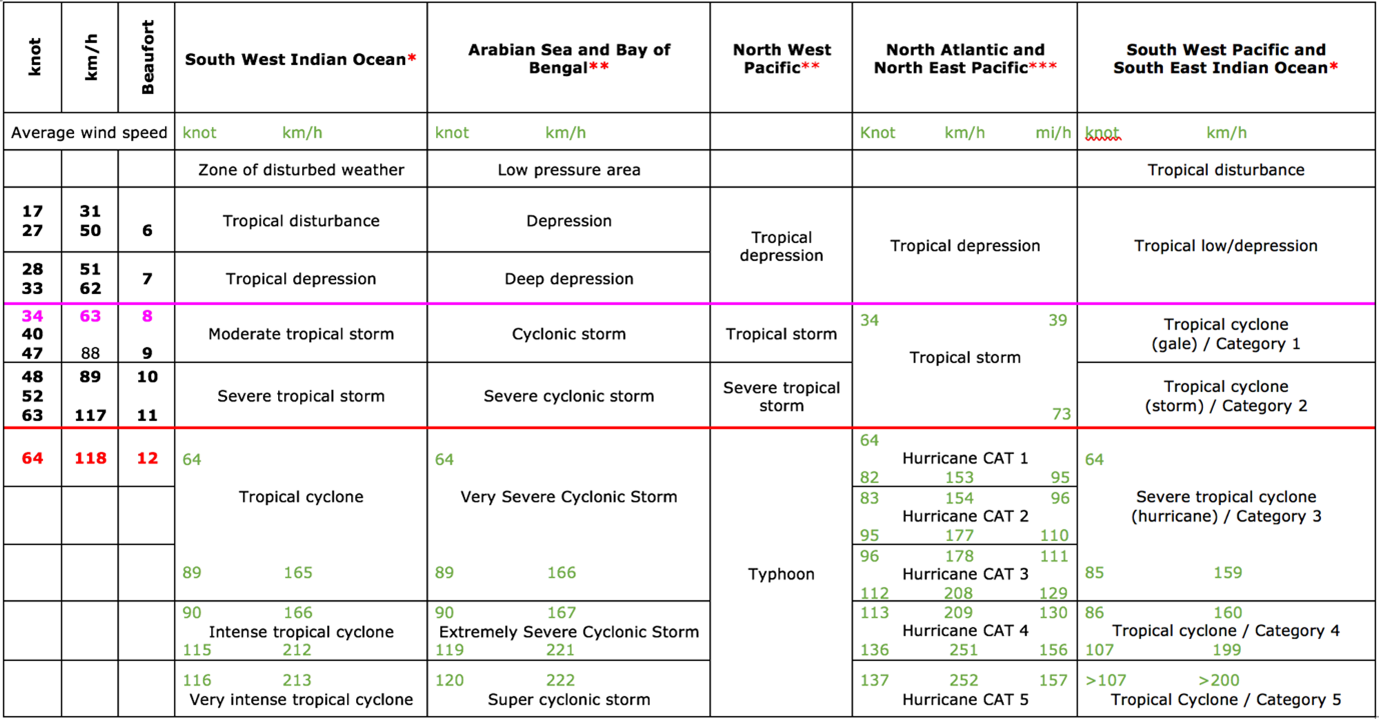

The development of a hurricane is classified by wind speeds into four stages: tropical depression, tropical storm, hurricane and major hurricane, with storms named once they reach tropical storm status (winds of 39mph or higher). An average season brings 14 named storms, 7 of which are hurricanes (wind of 74mph or higher) and 3 are major hurricanes (category 3, 4 or 5 with winds of 111mph or higher).

For 2025, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is now predicting a 50% chance of a more active season, with only a 15% chance of below-average activity. That translates to 13 to 18 named storms, with 5 to 9 of them becoming hurricanes, including 2 to 5 major hurricanes.

There are several factors for tropical storm development, but there a few key reasons why scientists believe it will be an active season: including neutral El Niño Southern Oscillation conditions, above-average ocean temperatures, and weak wind shear (little change in wind speed and direction vertically through the atmosphere). There is also the potential for a northward shift of the West African monsoon, and that could seed some powerful and long-lived Atlantic storms.

One year earlier, 2024 was overall an active season, with some notable storms, some of which spawned a significant number of tornadoes. Records were broken too, with Hurricane Beryl the earliest category 5 hurricane to form in the Atlantic on 2 July 2024. But the season then went strangely quiet, with only four named storms through the typical peak of the season (August/September). A northward shift in weather patterns in Africa was blamed before things changed again in late September 2024 with the arrival of Helene, which became the deadliest hurricane in the contiguous US since Katrina in 2005.

Helene brought catastrophic inland flooding, extreme winds, a devastating storm surge, and numerous tornadoes across an area from Florida to the southern Appalachians. Less than two weeks later, Milton formed in early October 2024 and underwent rapid intensification, with a 90mph increase in wind speed in just 24 hours.

Some years are more active than others. Looking further back, 2020 brought the most named storms in the Atlantic, with a total of 30; although 2005 saw more hurricanes, and three devasting category 5 hurricanes; Katrina, Rita and Wilma.

It isn’t currently clear whether climate change will increase the number of tropical cyclones across the globe, but a warmer world is very likely to bring both higher rainfall rates and maximum wind speeds.