Diary from Svalbard

Nowhere on Earth is heating faster than the Arctic. Broadcast meteorologist Laura Tobin visited Svalbard to look at the impacts of climate change, and what it will mean for us.

The British public has always been interested in the weather. But now, more than ever, they want to know more about how it works and why it’s changing. As a TV meteorologist I have always been passionate about including science in my daily breakfast forecasts on ITV. So I jumped at the chance to go to Svalbard to look at the impacts of climate change and broadcast live on Good Morning Britain from a glacier.

Situated halfway between Norway and the North Pole, the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard is about two-thirds the size of the UK. High in the Arctic Circle, Svalbard is dark for four months of the year and daylight was already shrinking quickly when we visited in September. It was important to travel to our broadcast positions during daylight hours, not least because of the polar bears! In just under a week we lost around 16 minutes of light a day, over an hour and a half of daylight.

There are no direct flights to Svalbard, so we flew to the largest settlement Longyearbyen via Oslo. Let me address the flying here, as some may raise the irony of flying (which is bad for the environment) to the Arctic to report on climate change. Why couldn’t I talk about it remotely from a nice warm studio? Well, firstly, our team was minimal (just myself, cameraman Ed and producer Ruth) and all of our flights were carbon offset. Secondly, our broadcasts were seen by millions of people, allowing me to demonstrate the impacts of climate change to a newer and wider audience.

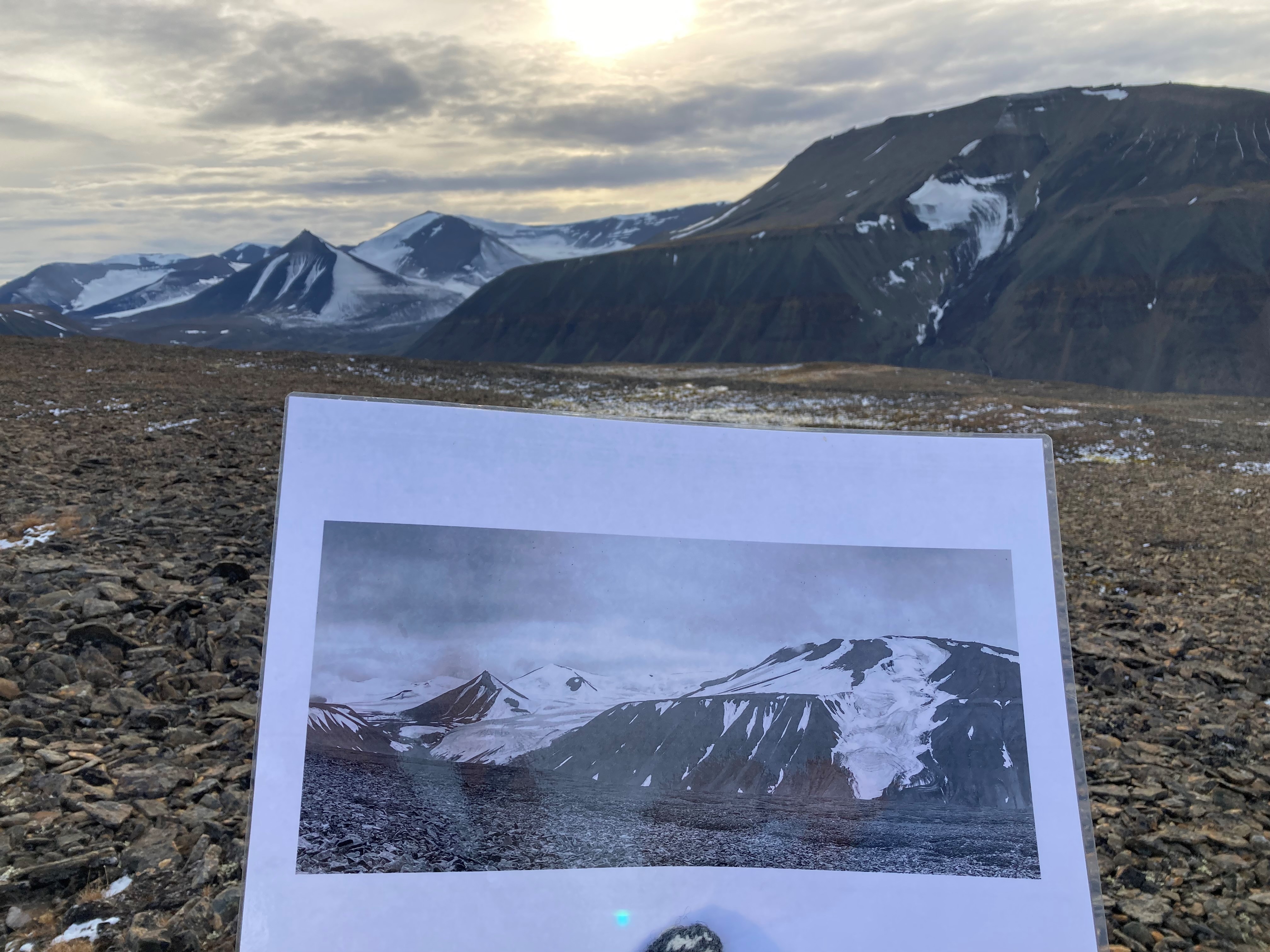

© Laura Tobin

On a personal note, I wanted to witness first-hand the impacts of climate change. Before I went, I felt I already knew the science and what it meant for the world. But the actual reality was eye opening, enlightening and alarming. I wouldn’t know what I know now or be able to share what I’ve learnt without being there in real life.

We were welcomed to Svalbard’s stunning landscape of jagged mountains, fjords and glaciers by our guide Arne Kristoffson. He arrived in Svalbard in 1980 as a coal miner; coal mining was huge in Svalbard as it is in Norway, but most of the mines are now closed and environmental laws protect the islands. Kristoffson drove us a short distance through Longyearbyne, past the most northerly hotel and most northerly pub. The town is in the shadow of mountains with no snow and a glacier in the distance. In the past there would have been snow tops and a closer glacier, even in September.

We had to walk to reach our first broadcast location, but it was slow-going crossing the small, shingle-like jagged rocks that moved with every step. After half an hour of walking Arne stopped and told us this is where the glacier ended in 1980. In the distance, some 500 metres away, I could see the edge of the glacier. A retreat of half a kilometre in just over 40 years, but that wasn’t all, and it wasn’t something I fully appreciated until I stood there. It wasn’t the horizontal retreat that was profound, it was the vertical extent. Back in 1980 the glacier would have been 5 to 10 metres above our heads, up to 20 metres high in places. A huge volume of ice from just one glacier has gone into the Arctic Ocean. Factor in other glaciers on other islands, and we can multiply this loss many times over. And it all contributes to rising sea levels.

© Laura Tobin

An hour or so later we reached the Longyear Glacier and confirmed we would be able to broadcast from the remote location. Up close the glacier was white and black, rather than the typical white and blue, as the layers of snowfall were interspersed with dust from the mountains during the windy months. When a glacier melts, a channel of melt water develops at the bottom and a river of water causes the middle of the glacier to collapse and the layers to fold in. A glacier has existed at Longyear for many thousands of years, but for how much longer?

Why glaciers matter:

- There has been a sustained long-term decline of glaciers, they are at their lowest extent in 2000 years

- Glaciers have lost more mass in the last decade than in any other in observed history

- Since the 1980s, glaciers have lost more than they have accumulated. It’s the equivalent of slicing off 24 metres off the top of an average glacier

- The Arctic lost 6000 gigatons of ice from 1993 to 2019, which caused a global average sea level rise of 17 mm

- Glacier melt has been one of the biggest contributors to sea level rise, responsible for 40 per cent of sea level rise in the last 100 years

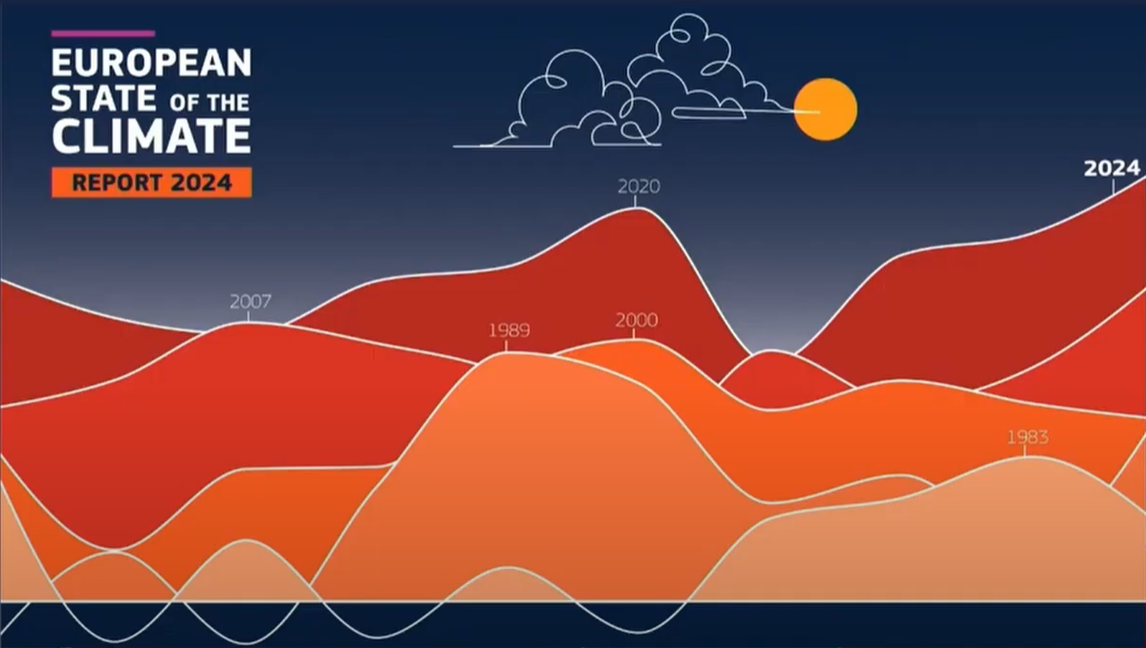

We know that Earth is overheating. Last year was one of the warmest ever recorded, the last decade was the warmest decade on record, and 19 of the top 20 warmest years ever recorded globally have happened since the year 2000.

Data from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute shows that in the last 50 years the average winter temperature in Svalbard has increased by 7.7 degrees from -15.9 °C to -8.2 °C, and the average summer temperature has increased by 2.5 degrees from +3.8 °C to +6.3 ° C.

Let me put that into perspective, over the past 50 years the Earth has warmed by an average of 0.88 °C. The UK has warmed by 1.24 °C, but Svalbard has warmed by 4.9 °C. We know the Arctic is warming two to three times faster than the rest of the world but in Svalbard, in the high Arctic, it is warming at least five times faster.

Nowhere else on Earth is heating up this fast.

More warming means the glacier retreat will only get worse. Current projections are that we could lose 50 per cent of glaciers by 2100. This will affect us in the UK. If all the glaciers on Earth melted, the average global sea level would be half a metre. That might not sound like much but it’s enough to put parts of the Humber, large swathes of Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, parts of Kent, and areas surrounding the Bristol Channel under water.

While in Svalbard we crossed the Isfjorden to visit the Borbreen Glacier. It was incredible to see this huge wall of ice 10 storeys high up close. Calving from such glaciers is a natural process of ice loss, but it is happening much more quickly and lasting longer. Isfjorden translates as ice fjord, but there is no ice. In fact, it hasn’t frozen in the past 11 winters.

© Laura Tobin

The Norwegian Polar Institute says that because of rapidly rising temperatures the Arctic ocean could be ice-free in the summer within 20 to 40 years. That means you could travel by boat all the way to the North Pole, and the ice will melt much earlier in the spring with freezing taking place later in the autumn. This will have devastating consequences for those on Svalbard, including the polar bears, reindeer and marine life, and will impact the rest of the world too.

The Arctic is one of the main drivers for the weather in the UK, meaning that warming here will change our weather. Our jet stream is driven by the thermal contrast between the warm air to our south and the cold air to our north. But if the cold air isn’t as cold, the contrast is less our jet stream is likely to weaken and meander, leading to ‘blocked’ weather patterns.

The ice itself plays an important role in cooling our planet; not because it’s cold but because it’s reflective. Ice has a high albedo – it reflects the suns’s rays back to space. But if the Earth warms, more ice melts so less heat is reflected back to space. Also, the ice-free darker sea or land will absorb the sun’s rays, causing warming which then leads to more melting. This becomes a vicious positive feedback cycle.

© Laura Tobin

Melting sea ice, glacier or ice sheets all have different consequences on sea level rise. Sea ice is like a floating ice cube in a full glass. It occupies the same area when it melts, meaning melting sea ice doesn’t lead to sea level rise. Glaciers are large bodies of ice on land, whose movement is influenced by gravity. As the glacier melts it goes into the sea and this leads to sea level rise (half a metre if all the glaciers melted). But ice sheets are a huge mass of ice on land. If Greenland’s ice sheet melted it would cause global sea level to rise by 7.2 metres. If the Antarctic ice sheet melted it would cause 70 metres of global sea level rise, mostly in the northern hemisphere. These high impact, low likelihood events are irreversible.

Even if we cut all emissions tomorrow, the melt will continue, sea levels will still rise and the environment will suffer. If we can limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, we can expect 2 to 3 metres of sea level rise over the next 2000 years. But if we warm by 5 °C, that will lead to 19 to 22 metres of sea level rise.

I’ve learnt that our actions are having a huge impact on the Arctic, and in turn what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic – it affects us all. The Arctic and the people there are amazing. We need to look after each other before the landscapes here are irreversibly changed, the wildlife gone forever, and global sea levels rise.

About the author

Laura Tobin has been a meteorologist for 17 years and is a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society. She has forecast for councils, the military and the public.

Laura Tobin has been a meteorologist for 17 years and is a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society. She has forecast for councils, the military and the public.

After 5 years at the BBC Weather Centre, Laura swapped to the other side and has ben presenting breakfast weather on Good Morning Britain at ITV since 2012. She is passionate about communicating climate change to a wider audience.