Summer air masses in the UK

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

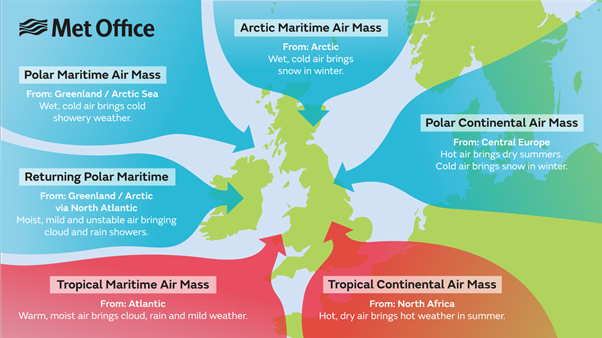

As a relatively small, mid-latitude island, the UK’s weather is at the mercy of the wind. Or rather the wind direction. Different wind directions bring air from different source regions, and it’s these air masses and their subsequent journey to reach you that determines the weather.

An air mass is a body of air with very little horizontal variation in temperature and humidity. They may cover several millions of square kilometres and extend vertically throughout the troposphere. The main source regions that allow air masses to reach their uniform characteristics are the high pressure belts in the subtropics and around the poles.

These source regions have distinctive characteristics; warm and dry air from the Sahara Desert, warm and moist air from the Tropical Oceans, cold and moist air from the Arctic and Southern Oceans, and cold and dry air from Siberia, Northern Canada and Antarctica.

The UK is affected by six major air masses from both warm (tropical) and cold (polar) regions, called Tropical continental, Polar continental, Tropical maritime, Polar maritime, returning Polar maritime and Arctic maritime. Their names reflect both their temperature and humidity profile, and each air mass brings typical weather and visibility to the UK.

We’ve previously discussed winter air masses, and which ones will lead to snow, but let’s take a closer look at what happens in summer.

Tropical continental

This air mass originates over North Africa and the Sahara and is most common during the summer although it can occur at other times of the year. It’s caused by high pressure over northern or eastern Europe with surface winds blowing from the south or southeast.

Tropical continental air brings our highest temperature – think July 2022 – but also poor visibility due to the air picking up pollutants during its passage over Europe and from sand particles blown into the air from Saharan dust storms.

While this wind direction usually means blue skies and heat, it can bring occasional thundery showers.

Polar Tropical continental

During the summer, an easterly wind from central Europe travels over much warmer land than in winter. So at this time of year we can classify Polar continental air as Tropical continental, as it brings warm, dry weather to our shores.

Tropical maritime

This mild but moist southwesterly air mass comes from the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean between the Azores and Bermuda. It usually occurs in warm sectors of depressions, between the warm and cold front associated with an area of low pressure, and during its passage over cooler waters becomes stable and quite saturated.

This results in a lot of low cloud and drizzle with hill and coastal fog. But it's not all gloom, as the summer sun can burn off the stratus cloud, especially to the lee of the hills, leaving warm and sunny if rather humid conditions.

Polar maritime

The most common air mass to affect the UK, this northwesterly air stream is usually found behind an Atlantic cold front. Although the air starts off very cold and dry in northern Canada and Greenland, during its long passage over the warmer waters of the North Atlantic it becomes unstable and picks up moisture. The result is frequent showers at any time of year.

In winter the sea is warmer than the land and showers are most vigorous over the sea, with hail and thunder common across much of northern and western UK. During the summer, land temperatures are warmer than the sea and the heaviest showers occur over eastern England.

Returning Polar maritime

Like Polar maritime this air mass has its origins over northern Canada and Greenland. However, it has taken a much longer sea track to reach the UK, first heading south over the North Atlantic then northeastwards. This often happens with slow-moving depressions in the mid-Atlantic. This is an example where you must trace the air mass back to its source, as despite appearing to be southwesterly like Tropical maritime this air mass is quite different.

During the long journey south the cold and dry air becomes unstable and moist but on moving northeast it passes over cooler water, making it stable in its lowest levels. The end result is largely dry with extensive stratocumulus cloud.

Arctic maritime

When high pressure sits over or to the west of Ireland and low pressure is over eastern Europe and southern Scandinavia, a northerly flow is set up over the UK bringing air all the way from the North Pole and Arctic Ocean. An Arctic maritime air mass is similar to a Polar maritime air mass but because of a shorter sea track the air stays colder and less moist.

We tend not to see it much in summer, but when it does expect heavy thundery showers and unseasonably low temperatures.

Ingredients for record-breaking heat

What do we need to get high temperatures? Location is key, with coastal or mountainous areas less likely to reach high values thanks to sea breezes or the cooling effect of altitude.

Inland towns and cities are warmer than the countryside, though sometimes it's the areas just downwind of an urban heat island that will break the temperature records.

The long sunny days and short nights of summer allow the heat to build, especially if the winds are light. Clear skies at night will allow more heat to escape so ideally a little bit of cloud at night will trap some of the heat built up by day.

As the ground dries up a higher proportion of the sun's energy will heat the air as it is no longer being used for evaporation. Most importantly, in order to get the heat in the first place we need to drag our air in from a warm direction, usually the south or southeast.

The synpotic set-up for high temperatures is an area of high pressure that will bring in very hot and dry Tropical continental air, plus if it remains stationary then the air stagnates and the heat builds up over a few days or even weeks.