40 °C in the UK?

Temperatures in the UK have never reached 40 ºC since records began. But at the end of June 2022, for the first time ever, weather forecast models started to show it as a possibility for mid July.

Currently, the highest officially recorded temperature in the UK is 38.7 °C, recorded at Cambridge Botanic Garden on 25 July 2019. Prior to that, the record was 38.5 °C, recorded on 10 August 2003 in Faversham, Kent, which beat the record of 37.1 °C set on 3 August 1990 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire. Before the 1990 heatwave, the record had stood for 79 years: 36.7 °C on 9 August 1911. And on 31 July 2020, the temperature reached 37.8 °C at London Heathrow airport, becoming the UK’s third hottest day on record.

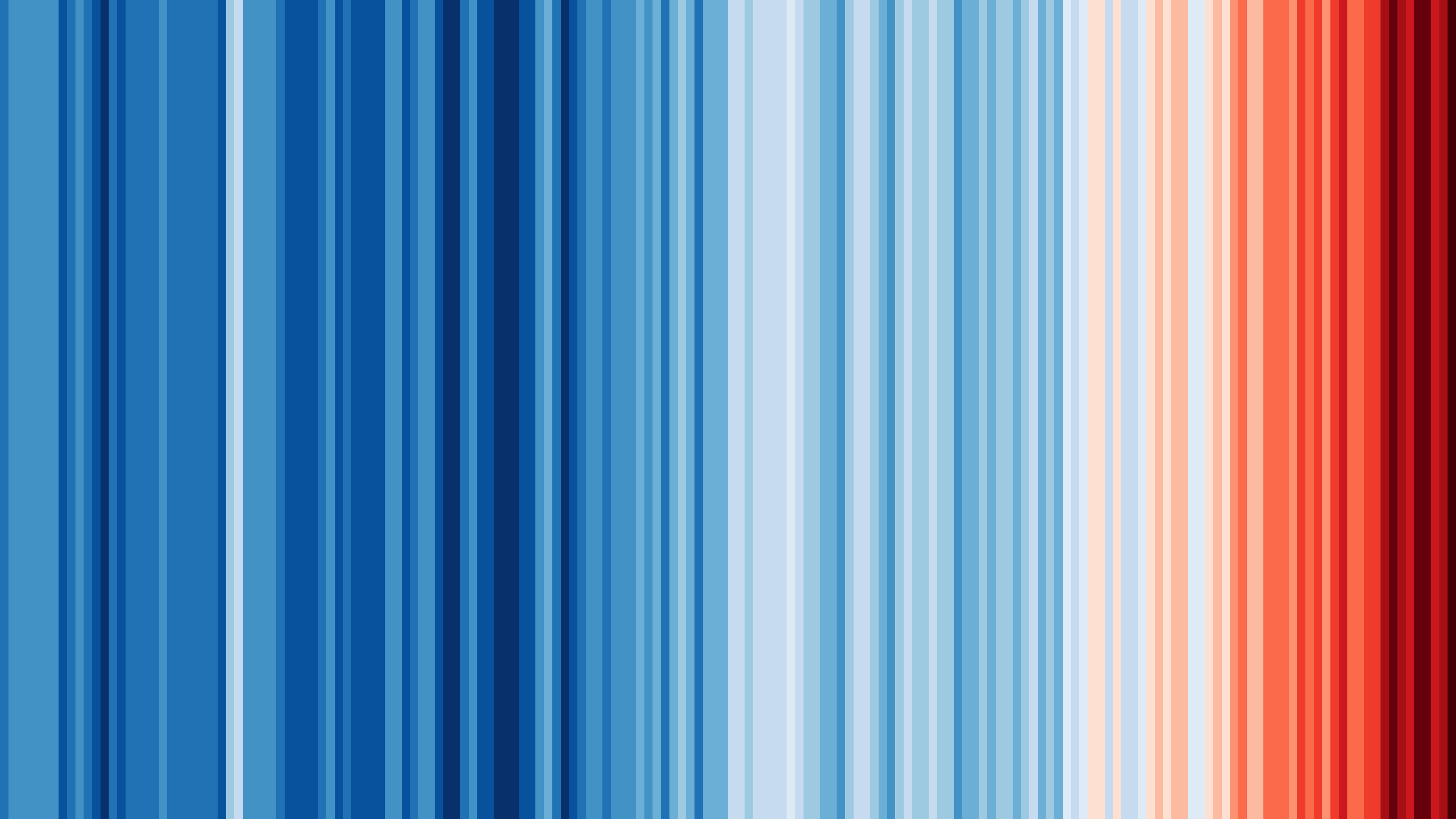

In our rapidly warming world, it comes as no surprise that we have observed more extreme heat in recent years. After the 2003 heatwave saw the UK surpass 100 °F (37.8 ºC) for the first time, attention turned to the 40 °C mark — which is becoming ever more likely due to human-caused global warming. Eunice Lo and Dann Mitchell provide a good overview of how climate change is affecting UK heatwaves in this open-access Weather briefing paper which formed part of the October 2021 COP26 Special Issue. More specifically, Nikolaos Christidis, Mark McCarthy and Peter Stott from the Met Office Hadley Centre wrote:

“The probability of recording 40 °C, or above, in the UK is now rapidly accelerating and begins to rise clearly above the range of the natural climate. The return time for the 40 °C threshold is reduced from 100–1000s of years in the natural climate to 100–300 years in the present climate and to only about 15 years by 2100 under the medium-emissions scenario…”

The increasing likelihood of temperatures above 30 to 40 °C in the United Kingdom (Nature Communications)

40° C in the UK still seems hard to comprehend. The UK has thus far only exceeded 100 °F on three individual days, and typically at very isolated locations. However, the same could have been said of reaching 20 °C in winter — something that had never been observed until a ‘winter heatwave’ in late February 2019. In June 2021, the Pacific Northwest heatwave obliterated local temperature records in Canada by as much as 4.6 ºC to reach a simply mind-bending record of 49.6 °C in British Columbia. To eclipse a prior record by such a margin showed what was possible in today’s world when all the 'favourable' factors come together, making 40 °C in the UK seem ever more plausible.

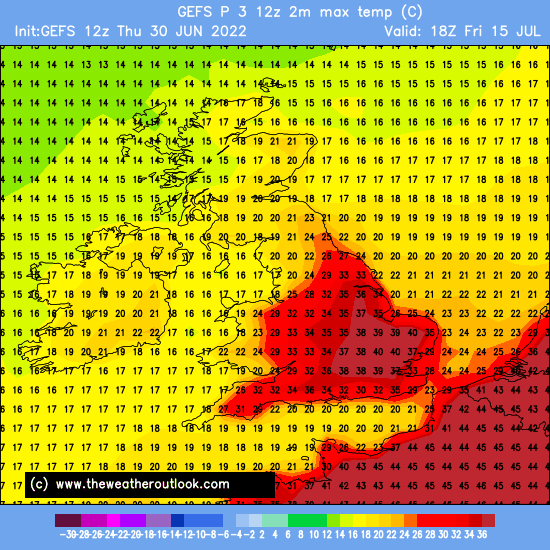

On the afternoon of 30 June 2022, output from the Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS), run by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) in the United States, showed the potential for never-before-seen heat in the UK. The GEFS produces a set of 31 alternate forecasts out to 16 days ahead to give forecasters an understanding of a range of possible scenarios. One of these 31 ensemble members showed the maximum temperature in southern England reaching over 40 °C on 15 July (see Figure 1).

As far as anyone I have spoken to can recall, this was the first time that 40 °C had appeared in a major global forecast system for the UK. It wasn’t even just the mere appearance of 40 °C that was remarkable — this forecast showed a huge area of southeast England surpassing 39 °C. Given that the UK’s previous hottest days had only seen 38 °C exceeded very locally, this was unlike anything anyone had ever seen before. Furthermore, site maxima are usually higher than what global models predict due to their relatively coarse resolution — so seeing a global model explicitly produce conditions that pulverised the existing records was not something I think anyone expected to see.

But that was just a single member of one ensemble forecast system. Ensembles are designed to capture a range of possible outcomes (even those which are very unlikely), and it’s common to see a single member do something a bit crazy — especially beyond 10 days. At long lead-times, errors in the model physics can occasionally lead to rapid error growth and produce unphysical outcomes. There can also be situations where the model has a bias or ‘drift’, whereby on average it tends toward a similar outcome at a fixed lead-time rather than a fixed valid date, and so the apparent forecast is always pushed back – like chasing a rainbow.

However, assuming that there is no unphysical model error or drift, the individual ensemble members can be considered as alternate realisations of the real world (like parallel universes). And if an ensemble member can be considered as an alternate version of the real world, then the real world can be considered as just one ensemble member – and so looking at ensembles gives us more opportunities to see what could happen. Thus, the appearance of 40 °C in that single ensemble member suggested it was a possible evolution over the next 2 weeks — but extremely unlikely.

During the following days, more forecasts continued to show 40 °C — or even more broadly, more members started to show >35 °C, which in a global model at that sort of lead-time would suggest the potential for a new UK maximum temperature record.

Historic, unbelievable chart.

— Dr Simon Lee (@SimonLeeWx) July 3, 2022

GFS 18Z with widespread temperatures of at least 41°C in England on 16 July. The current UK record is 38.7°C.

It is possible that the model has runaway warming in its surface layer. It is also possible that an unprecedented heatwave may develop. pic.twitter.com/REfK6z1qEO

It’s now over a week since that first extreme GEFS member showed 40 °C. In that time, we have also seen 40 °C appear as a possibility from forecasts generated by models run at ECMWF, which increased confidence that it was a realistic possibility and less likely due to model error:

As of today's 12 UTC run, the ECMWF ENS now clearly has ensemble member(s) with 40°C in parts of England, albeit a few days later than GFS/GEFS has been suggesting. It remains far from the most likely outcome, but this is no longer something confined to one prediction system 🫣 pic.twitter.com/GCJpqFc3GE

— Dr Simon Lee (@SimonLeeWx) July 6, 2022

All this said, what these forecasts all show is that truly extreme heat in the UK is not the most likely outcome, even if the risk is likely the highest it has ever been. For example, for the weekend of 16/17 July 2022, most forecasts are in the low-to-mid 30s and there are just as many forecasts showing maxima not much above 20 °C as there are showing 40 °C. A large part of this uncertainty remains because a specific evolution of the large-scale weather across western Europe is required in order to pump the warmest air from Africa, through Spain and France, and then into the UK. This involves the development of a low pressure system west of Iberia and its subsequent northward drift during next week, with warm air advection on its eastern flank.

This effectively has to happen perfectly for the UK to attain 40 °C. Extreme events are inherently unlikely; the real atmosphere only gets one chance to evolve over the next few weeks, and all our best models suggest that it is unlikely to go down the 40 °C path.

But the very fact that 40 °C in the UK has appeared repeatedly as a possibility from multiple forecast models suggests it is now very much something for which we need to prepare. Regardless of whether the UK does see an unprecedented heatwave this summer, we have entered uncharted territory in ‘forecast world’. Eventually, this will translate to the real world, and with the global climate continuing to heat up, we can expect to see more situations where 40 °C appears in forecasts for the UK in the coming years and decades.

About the Author

Simon Lee is a postdoc at Columbia University.

He became interested in weather during his childhood in North Yorkshire. For his undergraduate, he studied the MMet Meteorology and Climate Master’s degree at the University of Reading, during which he spent a year at the University of Oklahoma. After graduating in 2018, Simon remained at Reading to pursue a PhD in subseasonal stratosphere-troposphere coupling. Simon took up the position of Co-Editor-in-Chief of Weather in September 2020 and was awarded the Malcolm Walker Prize by the Society in 2021. He completed his PhD in October 2021 and is currently working on stratosphere-troposphere coupling and large-scale dynamics at Columbia University.

Simon is keen on public science communication and has over 12,000 followers on Twitter (@SimonLeeWx).