An artist’s view of the meteorology of Mallaig

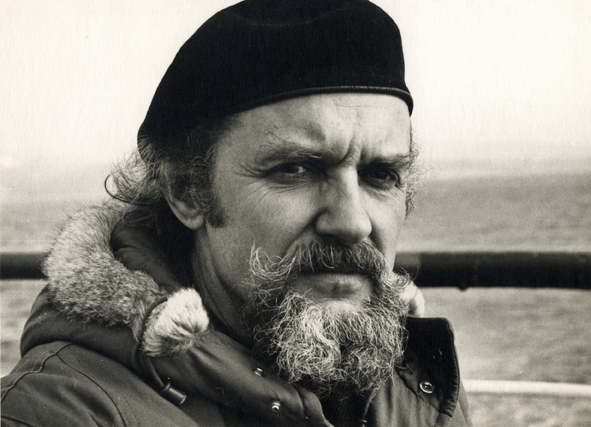

Dramatic skies and stormy seascapes have inspired many an artist over the years, such as the American Jon Schueler. His abstract paintings may not be a literal reproduction of the Scottish scenery, but can you spot the meteorology in his masterpieces? MetMatters asked Magda Salvesen, Schueler’s widow and curator of his estate, to select five of her favourite paintings and tell us more about them.

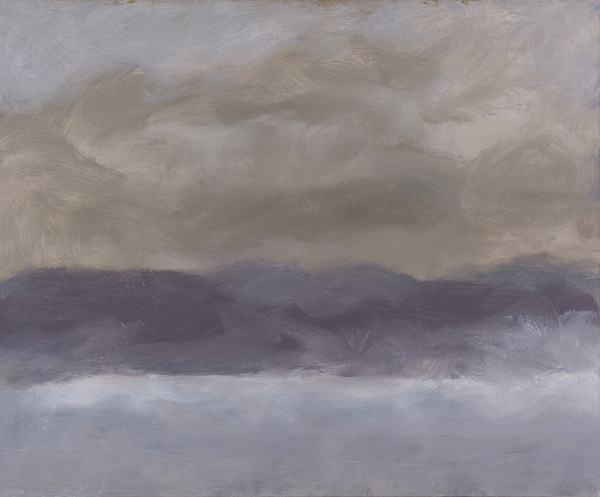

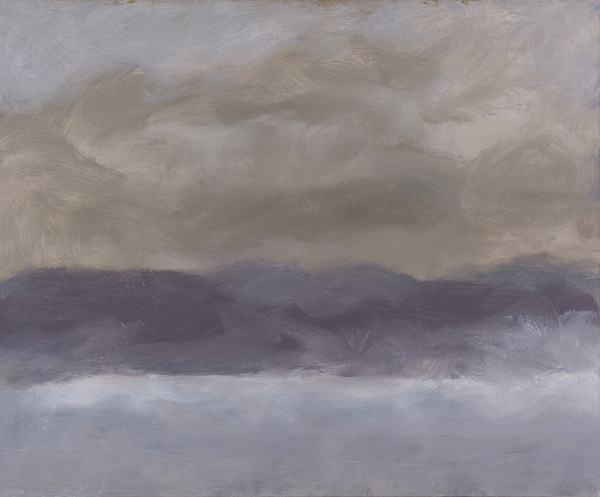

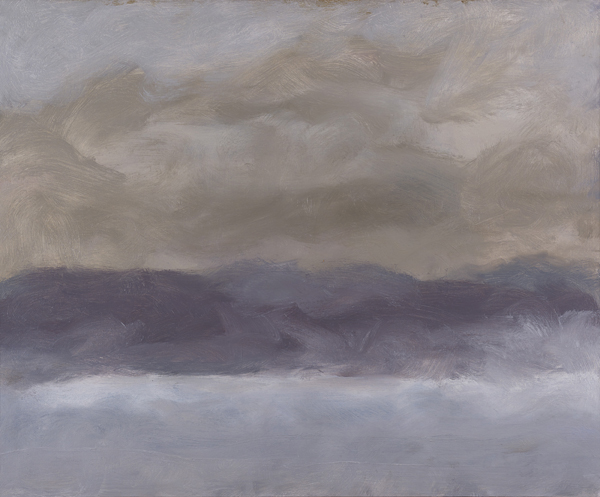

Cloud Over Knoydart

Magda Salvesen:

Jon Schueler’s first visit to Mallaig, Scotland, was during the harsh winter of 1957-58. His rented, non-winterised bungalow looked across Loch Nevis to the mainland peninsula of Knoydart, an area with no roads and reachable only by ferry or by a very long walk. His immersion in the weather and his confrontation with grand, unrelenting nature – oblivious of human beings rendered insignificant by this primeval landscape – was exactly what he sought: ‘I'm sure I've dreamed about it … and best of all, all sorts of colour in the sky, working in and out of that in the land, because the sky is just as raw and new as the land….”. [1]

Using palette knives, he thickly and expressively painted the interaction between the movements in the sky and water, however fleeting those shifts were. “I could stand in any one spot, and literally from minute to minute, quite often, the entire thing changes and what was real one minute has become effervescent the next and has formed into something else the following.” [2]

MetMatters’ meteorological musings:

The phrase “four seasons in one day” is often used to describe Scotland’s changeable weather. Indeed, it can feel like that when an Atlantic low-pressure system rattles through. The day might start off dry and bright, but the cloud thickens and lowers as the warm front approaches, its passage marked by a long spell of steady rain and an increase in temperature. Some sunny spells may develop in the warm sector between the warm and cold front before a narrow rain belt herald’s the arrival of colder air. After that it’s sunshine and blustery showers, some of which could be heavy with hail and thunder.

The Search: Summer Sky, Black

Magda Salvesen:

Romasaig, Jon Schueler’s studio in the remote Scottish fishing village of Mallaig, had, in the traditional way, its windowless gable end turned to the sea to protect the building from the force of winter gales. Therefore, he didn’t look directly out on to the Sound of Sleat and Isle of Skye but had to go outside to see which islands were visible and to check on the weather to the west and northwest.

In the 1970s, Schueler was especially absorbed in the horizontals formed by the geography of the Sound, but also by the way that the currents of water and reflections of sunlight from behind the clouds produced their own patterns. Mist often obscured the exact line of the coast of the Armadale Peninsula while clouds often completely obliterated the view to the formidable mountain ranges of the Black Cuillin and the Red Cuillin (sometimes for minutes, at other times for days on end). Looking into and looking beyond this juxtaposition of landscape and seascape, and searching for the possible presence of landforms through the endlessly intriguing and fleeting light, rain and clouds, Schueler became totally immersed in this area of Scotland.

MetMatters’ meteorological musings:

There is almost a wave-like appearance to the clouds in this painting that are reminiscent of Asperitas. This relatively new cloud formation was added to the International Cloud Atlas in March 2017. Closely related to undulatus clouds, Asperitas have well-defined, wave-like structures in the underside of the cloud, almost like looking at a roughened sea surface from below the waves.

The Sound of Sleat: June Night, IX

Magda Salvesen:

Jon Schueler’s June Night series of paintings stem from a specific summer night, at a time when the sun hardly sets in northern Scotland, and the light is often ethereal with no obvious source for the reflections and patterns seen in the water. As Schueler put it, “The vision was intensely real, yet it was the most powerful abstraction – Nature a cold, stately presence… the unearthly light, the dark shimmering of a streak below, a presence more powerful, more seductive, more real than man’s fantasy of poetry or joy or the damnation of his days”.[3] Although Schueler enjoyed what Mallaig people called the “beautiful” days – sun, blue sky, clear views, a relief from the otherwise near constant wind or rain – what intrigued him and fed his creativity was the power of nature experienced both through the violence and changeability of the weather and the silent, lonely, held stillness.

MetMatters’ meteorological musings:

Summer days are long in northern Scotland and the nights very short. In Mallaig the skies won’t get fully dark until nearly midnight in mid-June, and it isn’t long until the sun rises again. Even further north in Shetland, they use the marvellous phrase “Simmer Dim” to describe the twilight cast when the sun sets just below the horizon around the summer solstice. The very simple reason that Scotland gets more daylight in summer is due to its latitude. In the northern hemisphere, the summer solstice occurs when the North Pole points as far towards the sun as possible. The closer you are to the North Pole, the longer your day will be, around 18 hours in the Scottish Highlands.

Look into Red

Magda Salvesen:

After 1970, it was very important for Jon Schueler to return and live in the source of his imagery: Mallaig, Scotland. However, as he didn’t sketch or paint outdoors, work from photos, or see the expanse of the skies from inside his studio, what had excited him initially outside was transformed in recollection, and often in a series of variations. Exploring colour and depth of space, exulting in the movement of the brush and the flow of the paint, Schueler created abstract paintings that acknowledge nature but never depend on literal representation. This play or tension between competing ideas and the broad handling of the paint produces the complexity and excitement of Look into Red and is particularly apparent in Schueler’s work of the middle and late 80s. As he wrote, “I’m painting the dream of nature, not nature itself”.[4]

MetMatters’ meteorological musings:

The sky can take on glorious hues of yellow, orange, pink and red at dusk and dawn. The colours are created by Rayleigh scattering – the same phenomenon that makes the sky appear blue during the day. At sunset or sunrise, the sun’s rays travel through a greater distance of atmosphere to reach our eyes, which filters out most of the shorter blue and violet wavelengths, along with some green and yellow. That leaves us with the warmer hues of the red and oranges, leaving us with fiery-looking skies.

Blue Sound

Magda Salvesen:

Jon Schueler looked not at, but into, the skies. They served as a trigger for his memories and as a metaphor for disappearance and loss, but also as a stimulus for his own search for enlightenment and understanding. Although trained (in 1941 as a navigator on a B-17 bomber) to interpret the skies in terms of flying, he put aside the official terminology of the clouds: cirrus, cumulus, nimbostratus and so on, and saw them through his artist’s eye in terms of shapes and movements, density and colour, thus creating a mood beyond the actual science of weather. Here we might note that the word ‘sound’ in the title evokes not only a body of water, but a musical dimension. Schueler played the double bass as a Jazz musician in the 1950s and 60s, and he continued to listen to that music daily in his studio. The image of transience in the painting reflects the ephemeral quality of music as the voices of the instruments play off one another, different in length and density and tone.

MetMatters’ meteorological musings:

Clouds are given names according to their appearance (layered or convective), their altitude, and whether or not they are rain-bearing. Luke Howard’s classification system devised in 1803 is still going strong today, leading to 10 basic cloud types: cirrus, cirrostratus, cirrocumulus, altostratus, altocumulus, cumulus, stratus, stratocumulus, nimbostratus, and cumulonimbus. Convective clouds are as tall, or taller, than they are wide. They look lumpy and piled up, with tops like cauliflowers, and their names have the Latin root word “cumulo”, which means “heap”. They form when warm air rises, cools and condenses to produce the cloud. If the conditions are right, they can grow in height and size, eventually forming cumulonimbus clouds that can bring heavy and thundery downpours.

Futher reading and exhibitions

All references come from Jon Schueler's autobiography: The Sound of Sleat: A Painter’s Life by Jon Schueler, edited by Magda Salvesen and Diane Cousineau, Picador USA, 1999.

“When I speak of nature I’m speaking of the sky, because in many ways the sky became nature to me. And when I think of the sky, I think of the Scottish sky over Mallaig. It isn’t that I think of it that nationally, really, but that I studied the Mallaig sky so intently, and I found in its convulsive movement and change and drama such a concentration of activity that it became all skies and even the idea of all nature to me."[5]

A selection of paintings by the American artist, Jon Schueler (1916-1992), will be on display in London in Autumn 2022:

Coming up for Air: An Exhibition of Paintings by Jon Schueler

30 September - 28 October

Waterhouse & Dodd, 16 Savile Row, London

Jon Schueler: Reflections on the Sound of Sleat

29 September - 4 November

The Caledonian Club, 9 Halkin Street, London

Entry is free to all RMetS members.

[1] The Sound of Sleat, p23

[2] The Sound of Sleat, p23

[3] The Sound of Sleat, p189

[4] The Sound of Sleat, p194

[5] The Sound of Sleat, p96