Inside the Ice - What a French glacier taught me about climate change by Anita Vollmer

It is the middle of August in 2018 and I am in a small town in the Swiss Alps called Leysin. Beautifully situated in the mountains and not far from Lake Geneva, the temperatures here are in the mid-20s during the day, only to drop down to single digits at night. Leysin has a humid continental climate with annual precipitation averaging 1,481 mm, which equals more than twice that of London. Because the village is situated at an altitude of 1,565 m above sea level the average annual temperature is only 3.9°C. To make my way there, I have to cram myself and my backpack into a tiny rack and pinion railway to overcome the difference in altitude between Aigle and Leysin.

What has brought me to Leysin is a working group on Arctic Change organised by the German Academic Scholarship Foundation. Our group is composed of undergraduate students like me and lead by two experts in the field. We are exploring the natural and social science perspectives of the changing Arctic.

On the first day of our work we are immediately drawn into a world of snow and ice. Imagine traveling mentally from our Swiss village to Longyearbyen, a town in the Arctic with an average annual temperature of -5.6°C. Almost 4 million people live in the Arctic according to the Arctic Council. Many of these belong to indigenous groups such as the Saami or the Inuit. As our globe warms these people are particularly affected because the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the globe (ACIA). This has many impacts on the Arctic – sea ice and glaciers are melting, and thawing permafrost leads to coastal erosion which poses a threat to human settlements.

It is in our nature that experiencing changes make them more tangible than watching videos, looking at pictures and having discussions. However, our small group of enthusiasts in Switzerland would hardly be able to travel to the Arctic to see the Arctic Change ourselves. Or would we?

Right at the border between France and Switzerland at an altitude of 1,050 m above mean sea level lies a city called Chamonix, well-known for winter sports and rock climbing. From there you can easily ascend to the Mer de Glace (Sea of Ice) which is the longest glacier in France, situated on the northern slopes of the Mont Blanc Massif. It is, of course, not the Arctic, but well suited to gain an understanding of glacial retreat caused by climate change. We decided to go on a day trip and explore the Mer de Glace. When we arrived at the station overlooking the glacier, I was surprised by how small the glacier appeared. It was only when I noticed tiny ant-like figures crawling up the side of the ice - in fact people - that the immensity of this river of ice dawned upon me. This became increasingly clear as we slowly descended to the ice, and the glacier walls started rising up beside us.

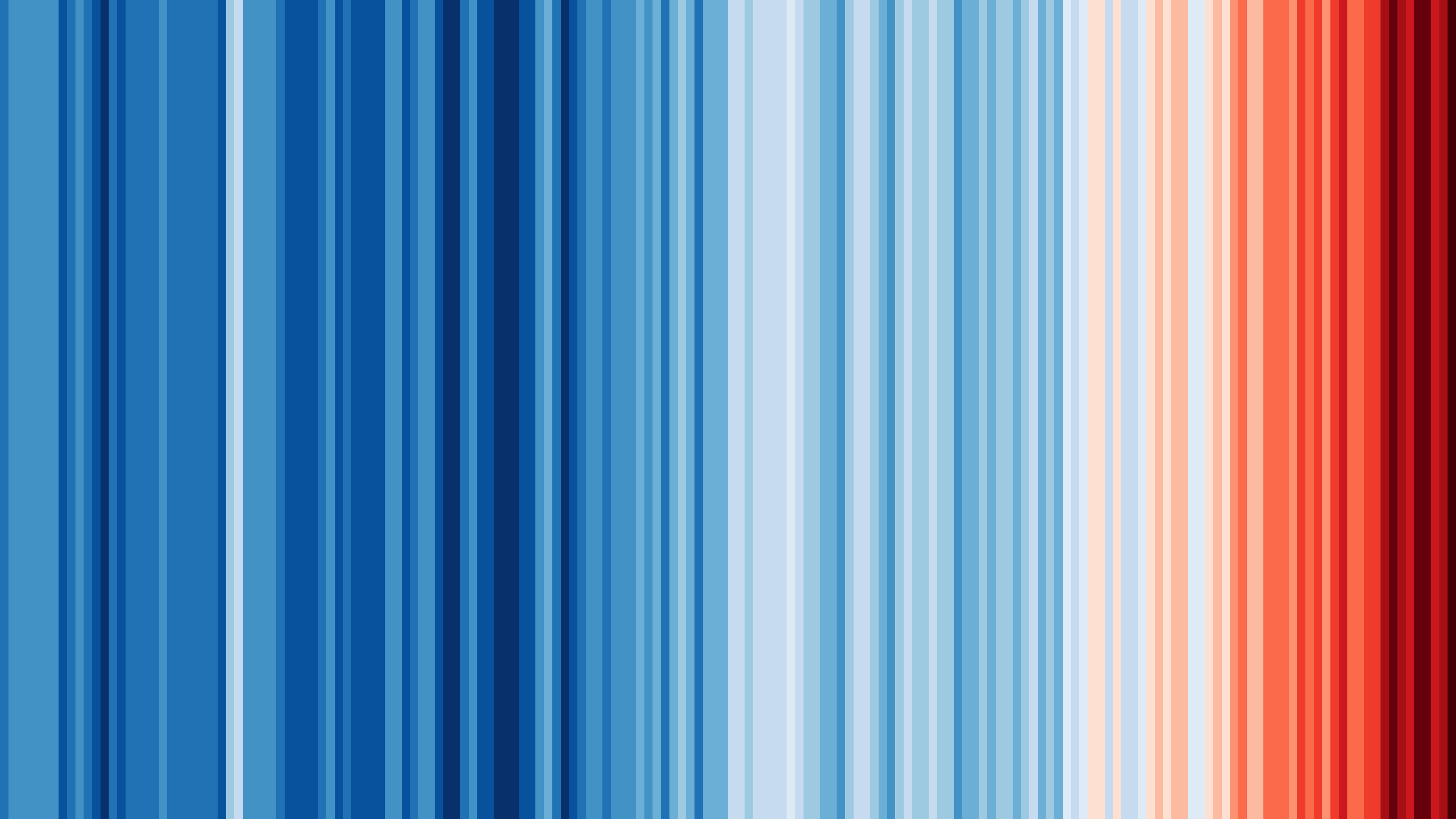

There is a small tunnel system excavated in the ice and so we were able to pass from the dirty-grey surface of the Mer de Glace into its shining interior. Walking through these tunnels of clear ice and being able to touch its cold, smooth surface with my bare hands was a breathtaking experience for me. However, the most memorable impression of the day was not the ice itself, but the descent. On our way down, we saw marks of where the glacier had extended to in earlier years. It was shocking to realize what enormous amounts of ice melted in just a few years. Since the 1820s the glacier tongue has retreated by about 2,000 m, and the glacier has lost 180 m of thickness. The Mer de Glace is currently retreating 35 m per year and this is not uncommon in the Alps. That is a dizzying speed for glacial movement. I study environmental sciences therefore I am confronted with the effects of climate change on a daily basis. Having such tangible proof right in front of me gave me a perspective that lecture halls and books never would have been able to.

It is easy to drift off into discussions about all the terrible developments caused by climate change, and media narratives are full of dire warnings. However, that is not my view of climate change. In my studies the solutions to climate change are emphasized over the problems. There has been great effort in investing in slowing down global warming, both in big and in small ways. The recent IPCC 1.5°C warming report has sent a renewed surge of urgency through the political landscape. This gives me hope that it is now a matter of how we can combat human-made climate change and not whether we should. And that some day a group like us will be able to enjoy the beauty of glaciers without being reminded of a phenomenon which threatens so many people around the world.

Anita Vollmer studies Environmental Sciences at the Leuphana University (Lüneburg, Germany).