The psychology of weather forecasts

What on earth has psychology got to do with forecasting the weather? Well actually, a lot more than you might think. I am a socio-meteorologist, working at the intersection of meteorology and social science. When I say that, I tend to be met with one of two responses: eyes lighting up with enthusiasm, or a very quizzical look. I completely understand the confusion.

When we produce a weather forecast, we’re not doing it just for the sake of predicting a future state of the atmosphere, we’re doing it because weather impacts us. It determines when we put our washing out, whether we wear a coat, our hobbies, our businesses and their operations, and our safety. We want to know what the weather will do, rather than what it will be. The Met Office’s purpose is ‘helping you make better decisions to stay safe and thrive’. This statement of intent puts people at the heart of our raison d’etre.

Social and behavioural science can offer insight all the way through the forecast process. Our forecasters (operational meteorologists) have vast amounts of data at their fingertips. How do they decide which data to look at, how to interpret probabilistic data, and what to do when data sources are conflicting? Are there human biases in the process? This requires an understanding of decision and behavioural science.

Another challenge that requires social and behavioural science insight is useful communication of forecasts and warnings. The most accurate forecast is of no benefit if not communicated effectively, and a precise and timely weather warning holds little value without clear, actionable advice. The recent (July 2022) unprecedented heat in the UK is an interesting example.

Psychology tells us that for many people, especially in the UK, hot weather is something to enjoy, not endure. We might have fond childhood memories of trips to the beach in the sunshine or splashing in a paddling pool during a previous heatwave.

But heat is deadly. Many meteorologists were accused of overhyping the heat and being alarmist; the science (and excess mortality data) tells us differently. Social and behavioural science warns us of the danger that by highlighting a hot spell, we encourage people to flock to the beach, increasing people's risk of sunburn, dehydration, water-related hazards, and possibly heat stroke. So we must clearly indicate advice.

Behavioural insights research shows that suggested actions should be listed ‘easiest’ first. It also tells us that in the case of heat warnings (as opposed to other weather parameters such as wind, snow, rain, fog etc.) that people are more likely to take action on behalf of someone else, so framing the advice in terms of helping vulnerable relatives and neighbours is most efficacious. This has the additional benefit that once people have taken this action, such as ensuring an elderly relative keeps their curtains closed during the day, drinks plenty of water, and doesn’t go outside during peak daytime heating, they are then more likely to take that advice on board themselves.

As @metoffice forecasts high temps this week, let's look out for each other during the hot weather - the heat can affect anyone, but for some, it can have serious effects on their health.

— UK Health Security Agency (@UKHSA) August 9, 2022

Find out more about how to #BeatTheHeat ☀: https://t.co/Tw1SQdhx86#WeatherAware pic.twitter.com/enCdAJRj2n

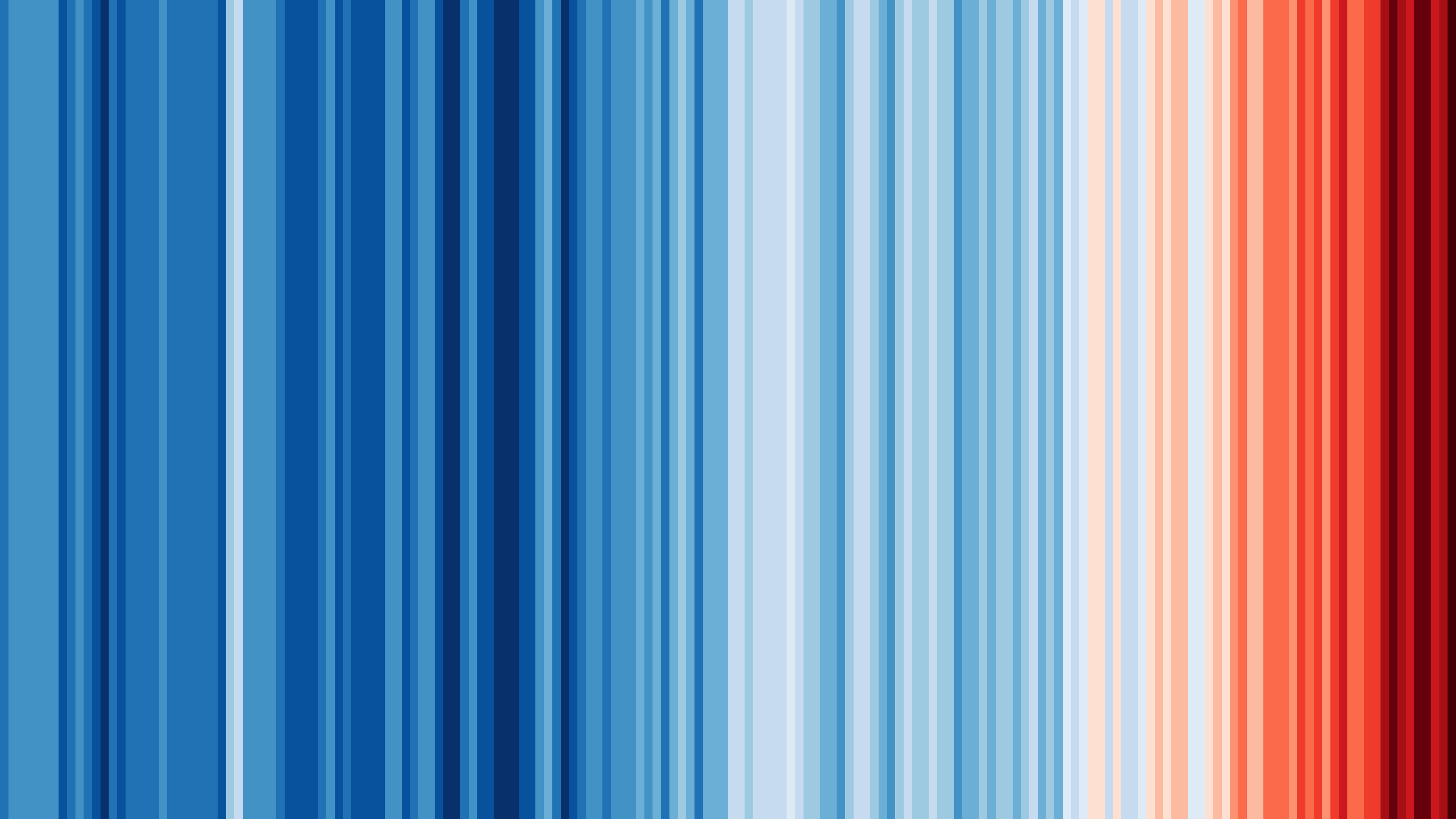

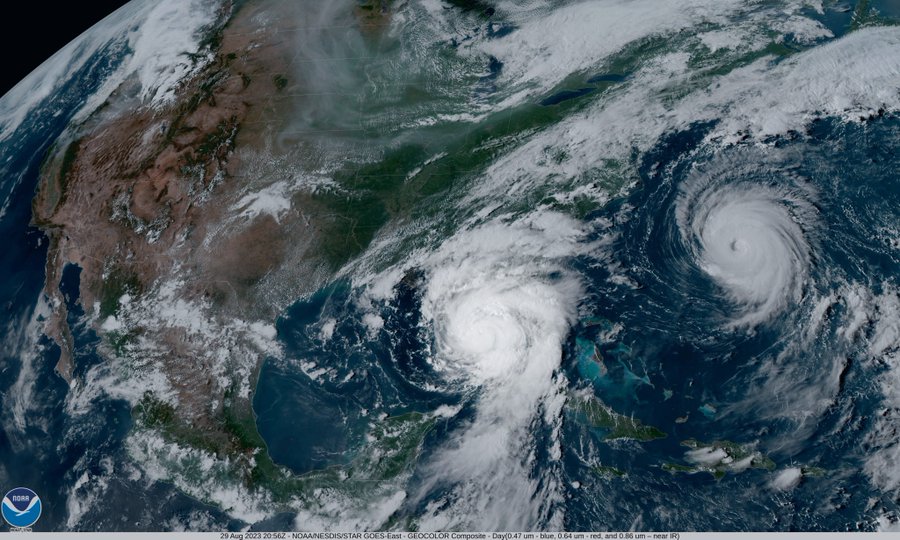

Of course, social science is an incredibly broad area, covering a vast array of topics that are relevant and useful – in fact vital – to meteorology and other environmental sciences. We can use it to help us effect change to reduce carbon emissions and encourage other environmentally sustainable actions. It can help us understand why people may be reluctant to take mitigative action in preparation for flooding, including social norms bias. We can use it to encourage effective leadership and community engagement in times of crisis including natural disasters. In fact, I wrote a dissertation for my psychology MSc on the topic of mental ill-health and PTSD resulting from natural disasters, and how we might prepare for what could be a catastrophic mental health crisis resulting from more extreme weather events due to our changing climate.

I could go on, but perhaps I’ll leave you to think about additional ways in which social and behavioural science can augment the physical sciences. Suffice to say, this is a rapidly evolving area that combines my three great passions of weather, social science and communication, and I’m delighted to be able to call myself the Met Office’s first socio-meteorologist.

About the Author

Helen Roberts is the first Met Office socio-meteorologist.

Helen joined the Met Office in 2003, and qualified as a forecaster a year later. She has worked across a variety of sectors within operational meteorology including military, commercial, aviation and media, including four years as a weather presenter for BBC Spotlight, and can still occasionally be seen on screen, including Ch5.

In 2019, Helen achieved the RMetS Chartered Meteorologist accreditation and is a fellow of the Society, having served a term on RMetS council, the editorial board of Weather, and even a spell as interim editor-in-chief of the journal.

In addition to her career in operational meteorology, Helen has also worked at the Met Office press office, in the college, and in the innovation team, before her recent appointment to the role of socio-meteorologist.