Scottish Snow Patches: The Vanishing Ice

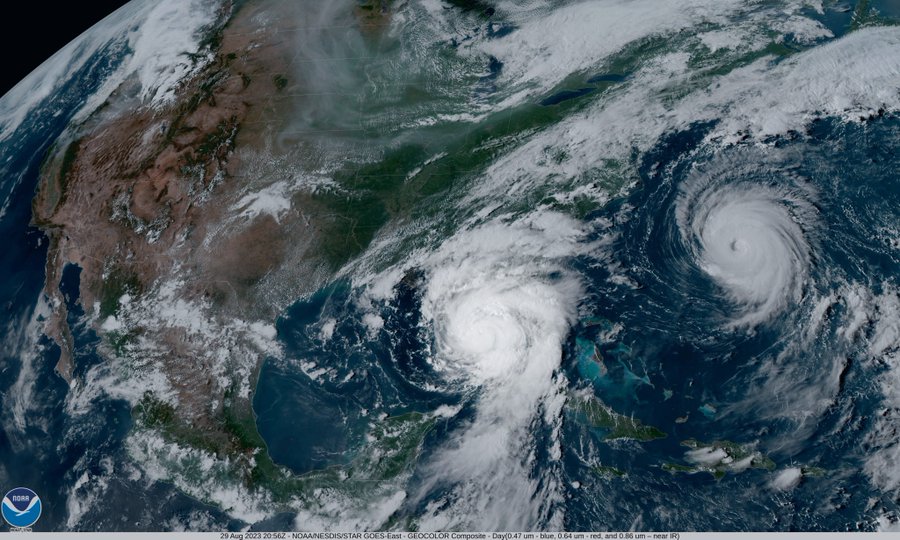

In 2018 a meteorological event happened in the UK that no one alive had seen occur before. Moreover, it is probably fair to say that this event had not been witnessed for, at least, hundreds of years previously – if not more. And whereas other weather incidents such as hurricanes, tornados, and record-breaking temperatures garner headlines, the event to which I refer would have passed entirely unnoticed save for the efforts of a small band of enthusiastic amateurs recording it.

The incident I am referring to relates to snow. Specifically, patches of snow. Even more specifically, a patch of snow that hitherto survived every year on Scotland’s hills from one winter to the next. The patch of snow in question is called ‘The Sphinx’ and resides in the innermost recess of the Cairngorms’ most isolated corrie, Garbh Choire Mòr of Braeriach. [1]

In days gone past, The Sphinx – so named in the 1940s because of the shape of the rocks situated above it – was thought to be permanent. We know this for sure because of the literature left to us by the far-sighted members of the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC). In late 1933 a member of the club wrote to The Times of London to advise that the patch had vanished for the first time in the memory of even the oldest member of the SMC. None of the fellows of the club, whose experience of this patch stretched well back into the mid-1800s, expected to see such a thing happen again. Alas, though, they were to be proved wrong.

Twenty-six years passed, with normal service resuming. The Sphinx survived through all these years unmelted. However, in late summer 1959 climber Sandy Tewnion went to Garbh Choire Mòr to do some climbing and noticed that The Sphinx had once again succumbed to the season’s warmth. He duly reported back this highly unusual occurrence to the SMC. Once more, however, the disappearance looked to be an anomaly, as all through the 1960s, 70s and 80s The Sphinx endured. But, in 1996, a tipping point seems to have occurred. For it was in that year that it vanished again, and it was to herald the start of an alarming increase in frequency. In 2003 it went once more, and then again in 2006. That was the third time in 11 years when it had only vanished twice in the previous 300. Something was definitely afoot. But worse was to come, and this takes us back neatly to that meteorological event that I mentioned at the top of this piece.

The Sphinx melted completely in 2017 and 2018. Two years in succession. The first time such a thing had ever happened. At the time those of us who study patches of snow on Scotland’s hills realised that this was a seminal event. We had – perhaps naïvely – assumed that the 10-year hiatus between the last complete melting in 2006 signalled a return to colder and snowier conditions. We were wrong. 2017 was an extremely snowless winter, and by June of that year we realised that we were looking once more at a similarly snowless Scotland come early autumn. 2018’s vanishing suggested that we were witnessing the first signs of a post-snow Scotland: something that 30 years ago would have seemed fantastical. To add to this thoroughly depressing sequence, The Sphinx also disappeared in 2021 and 2022.

So what does this tell us?

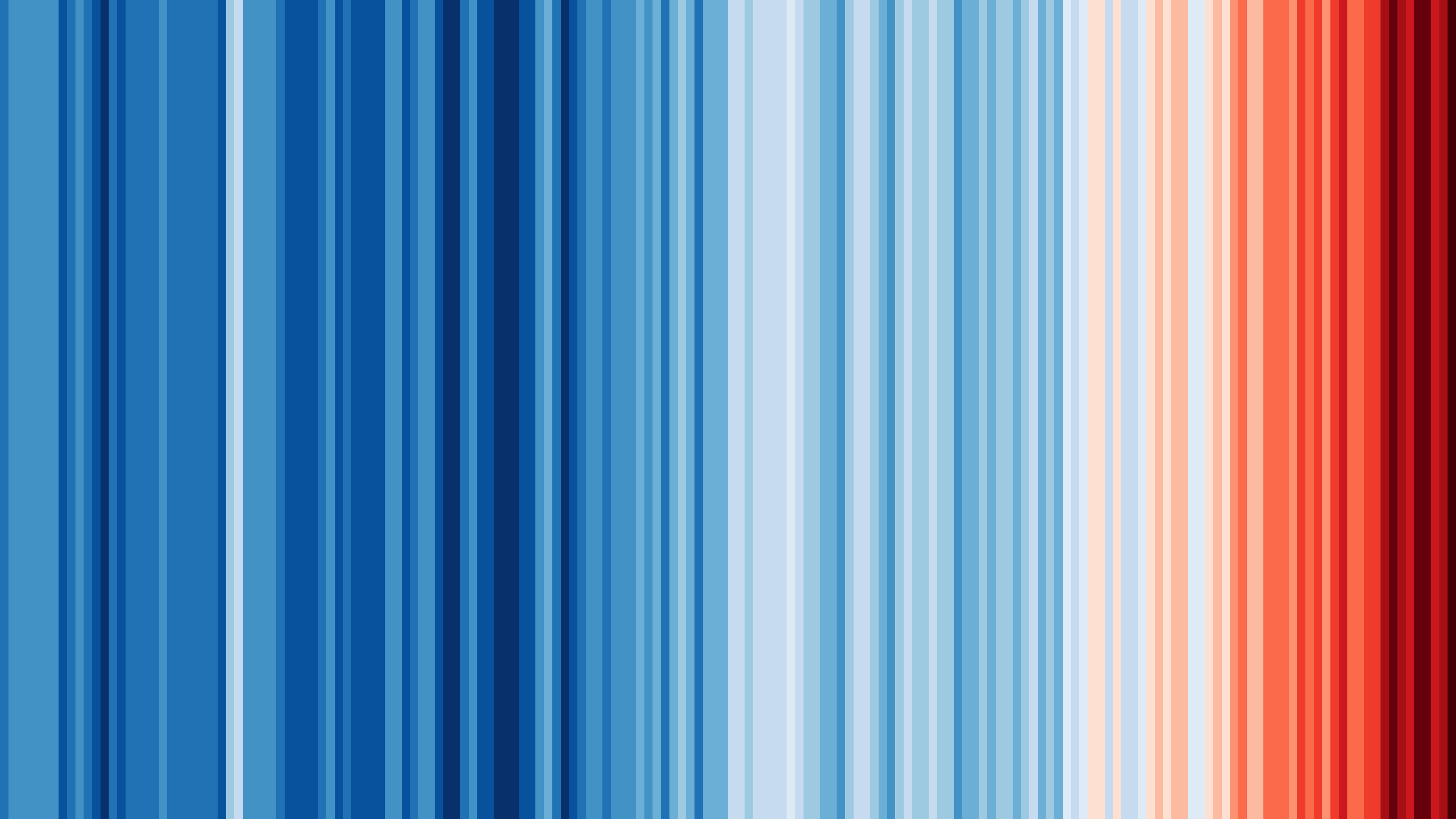

I am not a climatologist, nor even an academic. The study I am engaged in is done entirely as an amateur. I and people like me are citizen scientists, and we trudge to some of the country’s most isolated places purely for the love of it. Therefore, I tend not to try and get too involved in the science that lies behind it – not least because I have no qualifications to rely on. However, it does seem to me to be almost unarguable that a change in climate is almost wholly responsible for this shift in snow-patch longevity. It is also – surely – no accident that Scotland’s skiing industry is but a shadow of its former self. If one looks at the skier-days numbers of late compared to the 1970s and 1980s, far, far fewer people are going to our resorts. Though my own observations around snow-lie in general are anecdotal, it does seem to me that we get quite a bit less of the white stuff than we used to, even on the tallest of the Highland peaks.

In 2021 I had a book published called ‘The Vanishing Ice’. The title, arrived at via my agent and agreed on by the publisher, was not one that I was sold on. It seemed to me that it was overly pessimistic. However, the last two winters have shown me that there’s a very good chance that they, and not I, were correct. There can be little doubt that we are witnessing a shift in language used to describe patches of snow in Scotland. In days gone by the adjective that best described The Sphinx was ‘permanent’, but that had to change to ‘semi-permanent’, then to ‘perennial’ and then ‘semi-perennial’. But even this descriptor will not be able to withstand the pressure put on it by continual disappearance. We are now looking at an epoch where patches of snow are possibly going to be only occasional survivors.

As someone who is invested emotionally in this study to a degree that defies logic, this prospect makes me extremely sad. I will continue to go back to visit the location where The Sphinx reposes, but as each year passes it looks more and more like this will be a fool’s errand. This is a tale with little prospect of a happy ending.

About the Author

Iain Cameron is the author of The Vanishing Ice – Diaries of a Scottish snow hunter.

He has authored and co-authored 27 papers on patches of snow on UK hills, all of which have appeared in the Royal Meteorological Society’s Weather journal.

[1] A corrie is a glacial trough carved into the living rock, found in many upland ranges in Britain. Garbh Choire Mòr translates from Gaelic as ‘big, rough corrie’.