Svalbard's Sea Ice, where is it now? by Dr Michelle McCrystall

While a PhD student at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and University of Cambridge, BAS and the Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC) provided funds for a training course for a number of early career researchers to learn about fieldwork management skills. This training course provided the opportunity for a number of UK based PhD and PostDoctoral scientists to go to the Arctic to learn important fieldwork skills and to apply these to a number of projects which required fieldwork around Ny-Alesund, Svalbard.

Svalbard is a little-known archipelago at the top of the world which hosts a unique, dynamic and remarkably beautiful environment. These group of islands are situated in the Arctic Ocean between 76-81°N and are flanked to its west and east by the Greenland and Barents seas respectively. Almost half of the land here is covered in glaciers, and while it is one of the world’s most northerly settlements, the population of polar bears (around 3000) is greater than the population of humans. Despite the harsh climate of this region it is still is home to much life, alongside polar bears one would find Arctic foxes, hares, reindeer, whales (amongst other animals – these are the only animals I saw, minus the polar bears!) and over 1000 plant species which impressive for a region with large regions of permafrost, low temperatures and little precipitation.

However, while on this trip, I saw and learned first-hand about how things were changing from those who lived there and have experienced these rapid changes. Part of the work the group and I conducted while in Ny-Ålesund was to survey a local glacier. One element of our investigations was to replicate photos taken of the glacier 10 years ago and to compare them to each other. From this, we could see strong evidence of glacial retreat. While there, I also spoke to those who have lived and worked in Ny-Ålesund for over 20 years who told me that in the last few years they noticed great changes, particularly with the sea ice which is much thinner than before, and sometimes doesn’t really form in the winter at all.

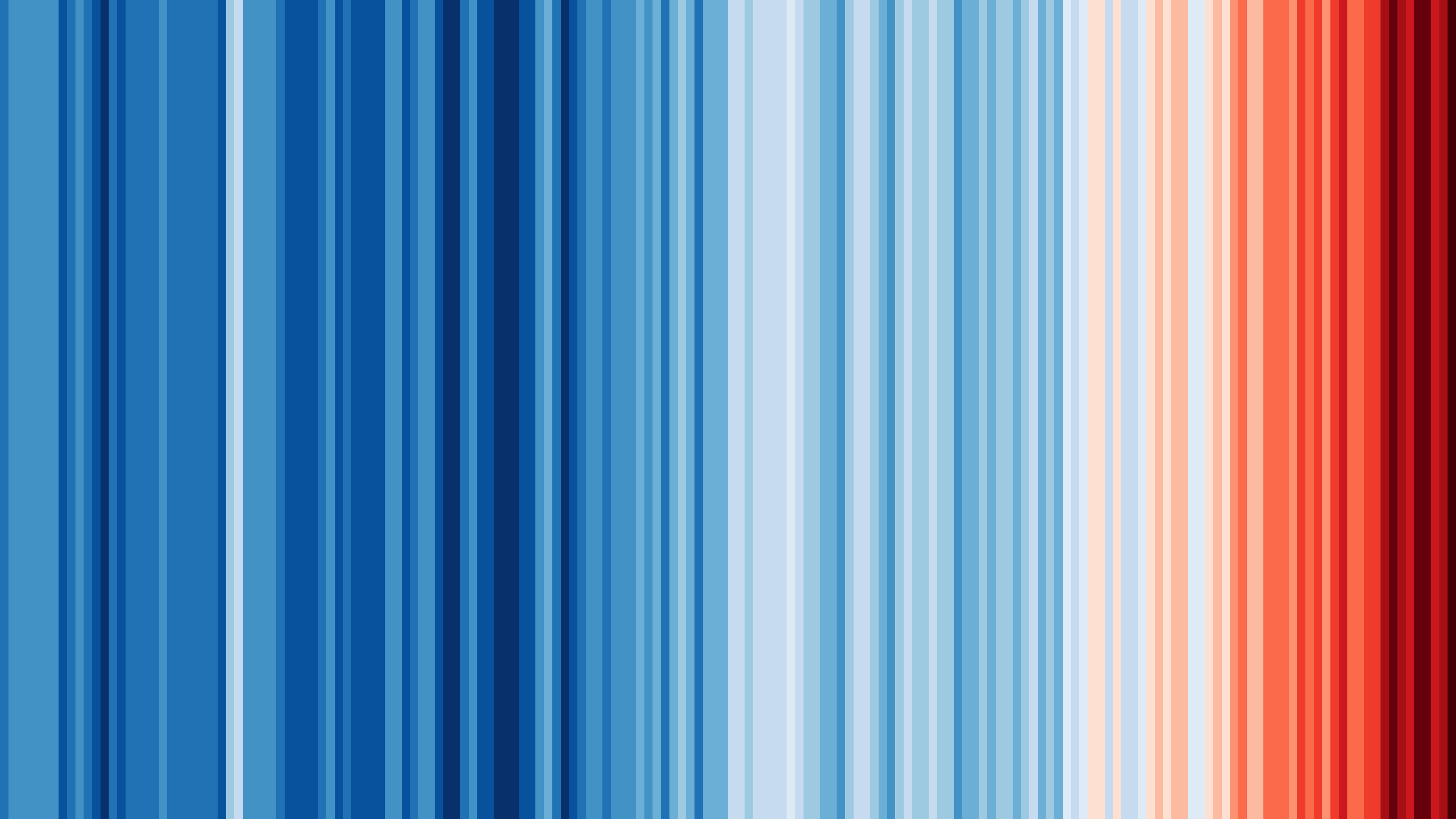

This trend of retreating sea ice is common across the entire Arctic region, mainly in summer/autumn months. The current rate of decline of Arctic sea ice extent in September (the month when sea ice reaches a natural minimum) in 12.8% per decade relative to the 1981-2010 average as shown by the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC). This has largely been attributed to ongoing climate change, however, both atmospheric and oceanic circulation, as well as natural variability, play a role in sea ice decline. Not only has the extent of sea ice declined but also its volume, meaning that sea ice is getting thinner, rendering it more susceptible to further melt. Greater sea ice melt results in more open water, which absorbs heat from the atmosphere and can result in more sea ice decline.

While the most rapid decline of sea ice occurs in summer, winter sea ice decline is also occurring, particularly to the north of Svalbard and in the Barents Sea directly to its east. Winter sea ice to the north of Svalbard has been rapidly declining by about 10% per decade and sea ice extent in the Barents sea has decreased by 0.43x106 km2 since 1979 which is around one-third of the extent in the pre-satellite mean era (before 1979). In fact, large regions of the Barents Sea have experienced ice-free conditions in recent years (Onarheim et al 2014). One of the primary reasons of sea ice decline in this area is believed to be ocean heat circulation from warm Atlantic water which flows from the Atlantic, along the Fram Strait, to the west of Svalbard, and across the north of Svalbard. Atlantic water has warmed by 1.1°C since 1979 and having a warmer ocean, with its greater thermal capacity than air, may result in more melt underneath the sea ice and more importantly delay the refreezing due to the warmer ocean temperatures. With warmer oceans and atmospheres, the future of sea ice in the region may be bleak with a recent study indicating that a year-round ice-free Barents Sea may occur between 2023-2036 (Onarheim and Arthun 2017), however this is still very uncertain but nonetheless gives an indication of the worrying negative trends of sea ice in the region.

So, as we busy ourselves in preparation for winter here in the UK, remember that as we defrost our cars and potentially curse the cold air, remember how vital it is in Svalbard and in the Arctic to maintain sea ice and a habitat for so many that rely on its stability.