10 weather terms people often get wrong

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

In the meteorological world we have surprisingly strict definitions for a host of weather-related phenomena. And confusingly some of these can vary between countries. Read on to find out what the polar vortex actually is, the difference between rain and showers, and why it’s redundant to say “a tornado touched down”.

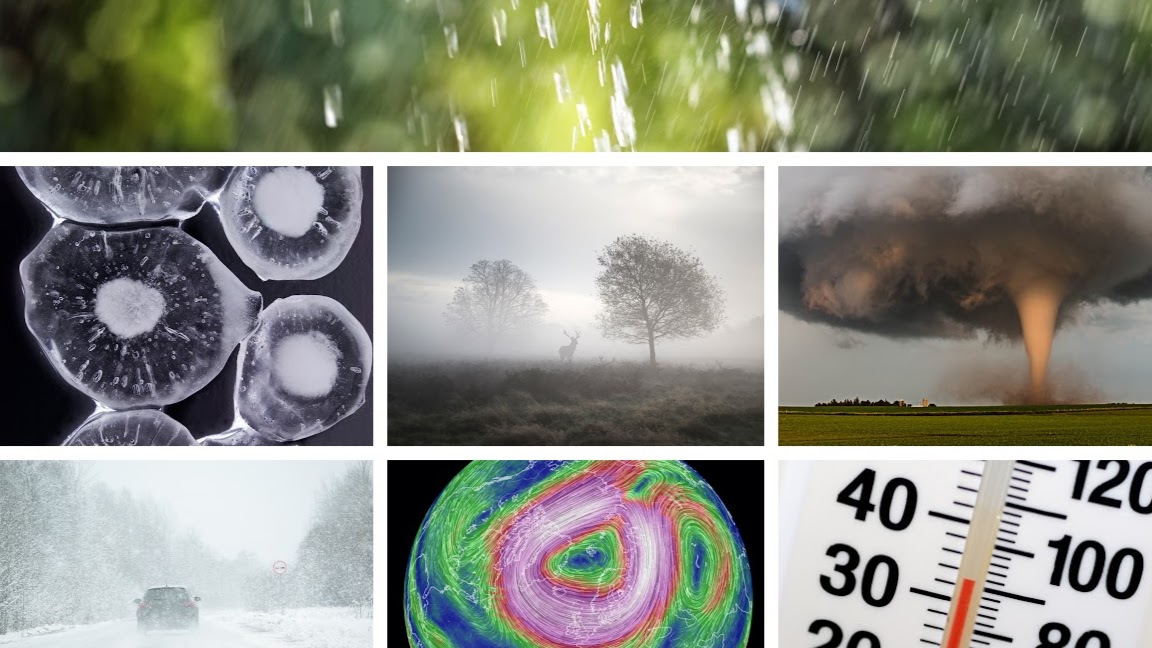

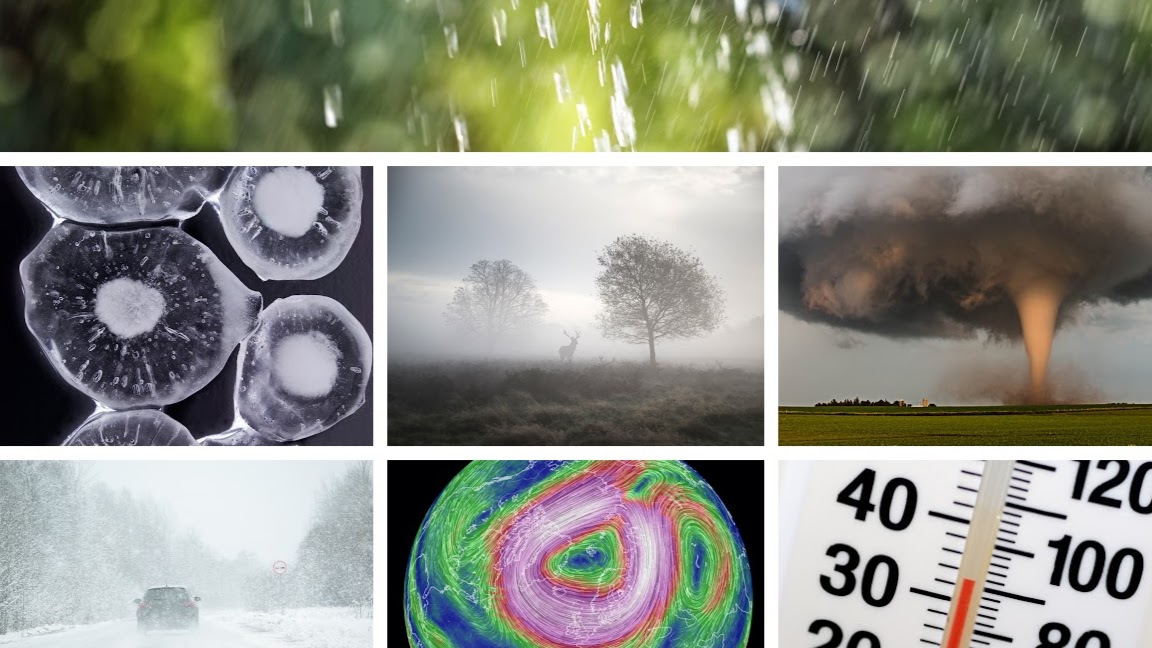

1. Blizzard — yes it’s a combination of strong winds and moderate or heavy falling snow (either continuous or in the form of frequent showers) but, more precisely, the winds have to be at least 30 mph (48 km/h) and the visibility has to fall below 200 metres for a snowstorm to be a proper blizzard.

2. Sticking with visibility – do you know your mist from your fog? It's all to do with how far you can see. If the visibility is less than 1000 metres then it's fog; if you can see more than 1000 metres then it's mist. As for the adjectives, dense fog is for visibility below 50 metres, thick fog is 200 metres, and under 1000 metres is often referred to as aviation fog. “Heavy fog”? Not a meteorological thing.

3. Same applies to “heavy wind”. You can use high as an adjective, or make your meteorologist happy and use the appropriate description from the Beaufort wind scale, matching the correct wind speed to moderate, fresh or strong breezes. And there are more wind definitions that get misused on a regular basis. Take gusts. A sudden, brief increase in the speed of the wind. This rapid, short-lived increase needs to be at least 12 mph (19 km/h) higher than the mean wind speed. Gust’s longer-lasting cousin is a squall, where the sudden increase in wind speed lasts for one minute or longer, and jumps up at least three levels of the Beaufort scale, rising to F6 or more (or increasing at least 16 knots and sustained at 22 knots or more).

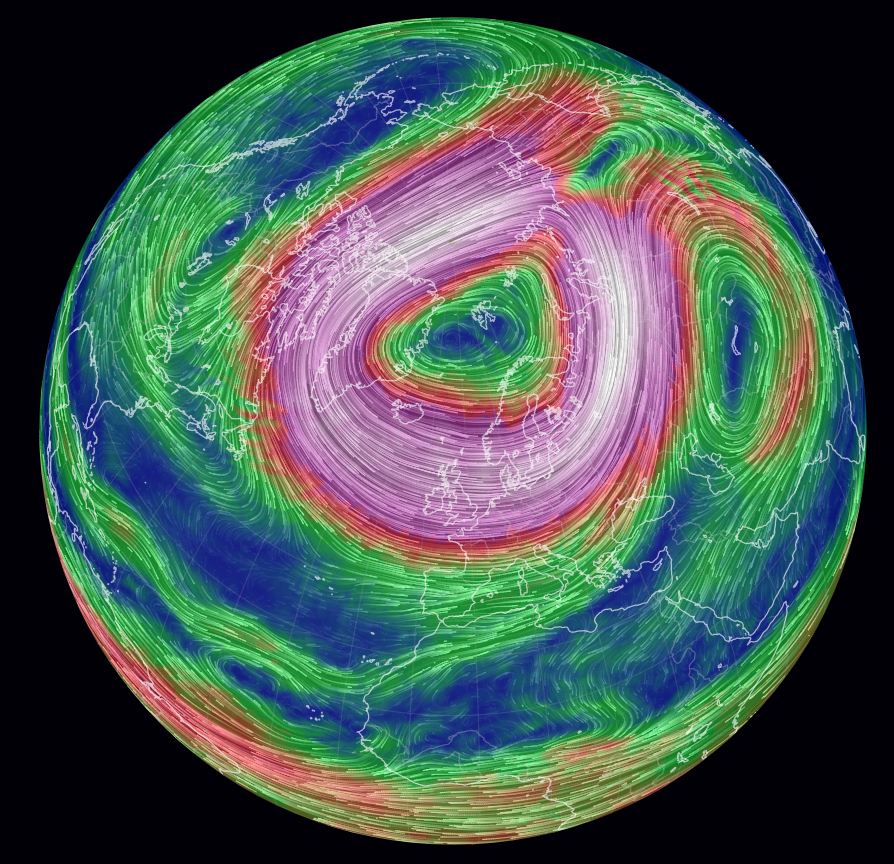

4. Polar vortex. A popular one for click-bait headlines, but often misused. The polar vortex is a circulation of strong winds (often in excess of 155 mph/250 km/h) high up in the stratosphere (10 to 30 miles above the surface) that circles the very cold air that surrounds our poles during winter. The polar vortex can strengthen and weaken, and these changes can affect our weather lower down in the troposphere. But don’t believe those headlines that claim you are IN the polar vortex or that it’s a “storm”.

5. Rain or shower? Do you know the difference? Do you care? Of course you do, you are reading MetMatters after all! The simple answer is the type of cloud they fall from, which in turn explains their characteristics. Rain falls from layered stratiform cloud, often associated with weather fronts. These clouds are large scale and cover the sky. The rain is widespread and lasts a few hours or more. Showers fall from puffy convective cloud, they are localised and can be intense. Showers are often hit and miss (your garden can get wet while your neighbour’s does not) and showers usually don’t last as long. But it isn't always so simple, you can get light and patchy rain and if the wind direction is just right you can get shower after shower making it more like a longer spell of rain. Of course – both will make you wet.

When it comes to distinguishing between rain and drizzle, size matters. Drizzle drops are smaller than 0.5 mm, but that’s pretty tricky to measure. A good tip is that if you can’t feel the drops but you are getting wet then it’s drizzle. Also, drizzle reduces visibility as the smaller droplets hang in the air for longer.

5. If you’re ever tempted to describe a downpour as a monsoon, just a reminder that the word monsoon actually describes the wind, more properly a shift in the prevailing winds that often causes a very rainy season or a very dry season. The word monsoon is derived from the Arabic word mausim (season of winds), where the winds of the Arabian sea blow from the northeast for one half of the year and from the southwest for the other half. The seasonal reversal of winds will draw moisture into areas that are normally dry, hence we often associate the word monsoon with torrential rainfall.

6. Hail or graupel and the real meaning of sleet. Winter precipitation can be confusing so here’s a quick overview of which is which. Hailstones are pieces of ice that form in vigorous convective clouds. Graupel, which looks like tiny polystyrene balls, can be mistaken for hail, but it’s actually formed differently. This “soft hail” is actually partially melted and refrozen snowflakes, where supercooled water droplets have added an opaque layer of ice or rime. And then there’s sleet. In the UK, sleet mainly refers to a mixture of snow and rain or snow that partially melts as it falls below the cloud. However, in some countries sleet refers to ice pellets. These are small translucent balls of ice, smaller than hailstones, that form as snowflakes melt into rain and then re-freeze as they fall through colder air. This results in a grainy snow pellet encased in ice.

6. Hail or graupel and the real meaning of sleet. Winter precipitation can be confusing so here’s a quick overview of which is which. Hailstones are pieces of ice that form in vigorous convective clouds. Graupel, which looks like tiny polystyrene balls, can be mistaken for hail, but it’s actually formed differently. This “soft hail” is actually partially melted and refrozen snowflakes, where supercooled water droplets have added an opaque layer of ice or rime. And then there’s sleet. In the UK, sleet mainly refers to a mixture of snow and rain or snow that partially melts as it falls below the cloud. However, in some countries sleet refers to ice pellets. These are small translucent balls of ice, smaller than hailstones, that form as snowflakes melt into rain and then re-freeze as they fall through colder air. This results in a grainy snow pellet encased in ice.

7. Storm chasers pursue severe weather, often in the hope of witnessing a tornado. These begin life as a funnel cloud that develops at the base of a thunderstorm. This rotating column of air extends from the base of the cloud towards the ground, becoming a tornado when it touches down over land, or a waterspout over water. So there’s no need to say a tornado touched down, as by definition all tornadoes must touch down or else they’d still be a funnel cloud.

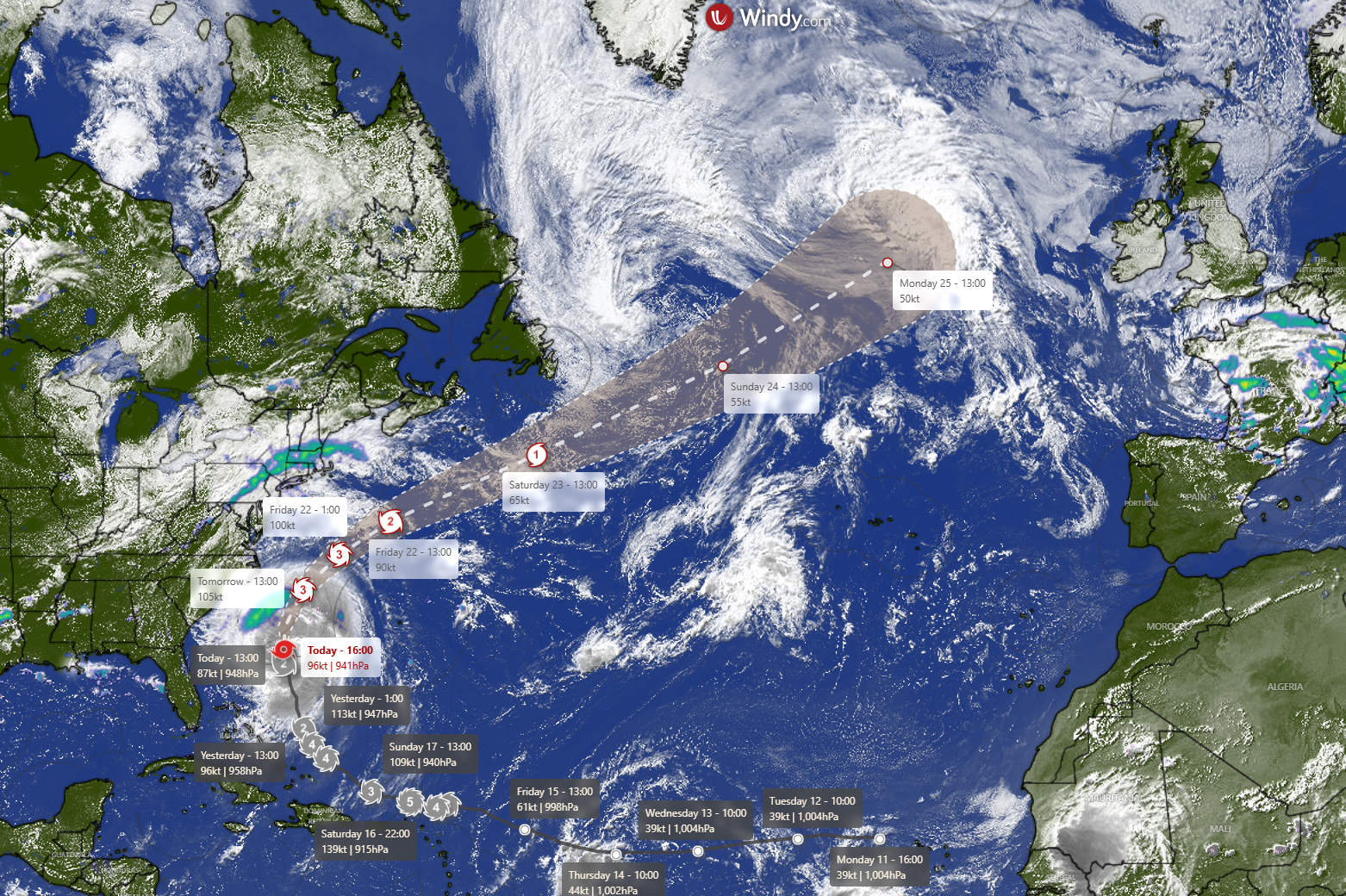

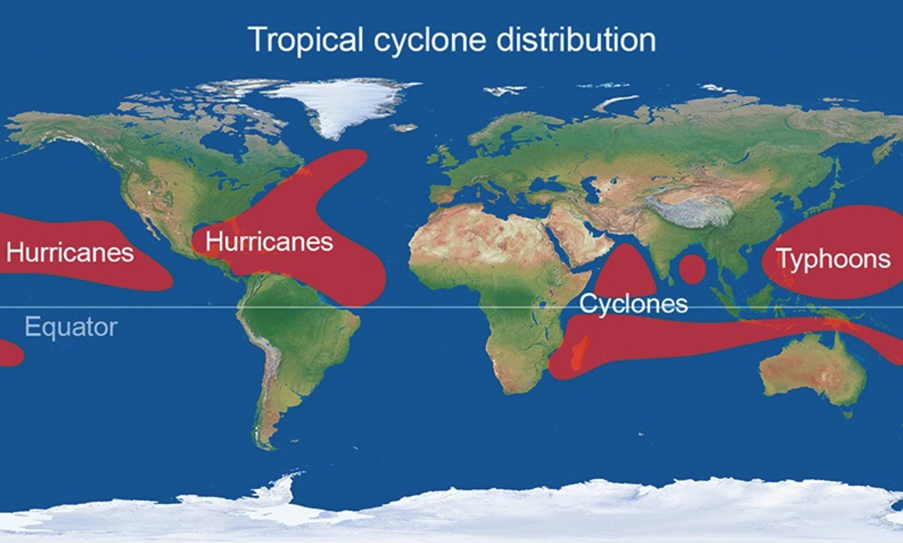

8. Are tornadoes the same as hurricanes? No — they are formed in a completely different way, plus tornadoes are much smaller and don’t last as long. In short, tornadoes are smaller, shorter-lived storms that form from thunderstorms, while hurricanes are large, long-lasting storms that form over warm ocean waters. So what’s the difference between tropical storms, cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes? Not a lot! The different terms hurricanes, typhoons and tropical cyclones all refer to tropical storms. They are named differently depending on the region they occur in. In the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific oceans, they are called hurricanes, whereas they are known as typhoons in the Northwest Pacific. Tropical storms are referred to as cyclones in the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean.

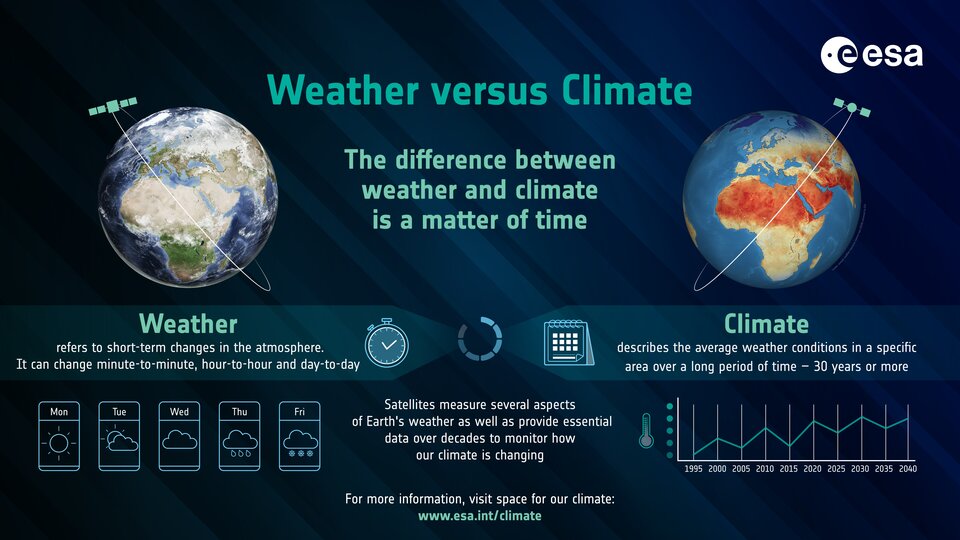

9. Sometimes people get confused between weather and climate, they are closely related but on different time scales. Weather is what we experience day to day, while climate describes average weather conditions over a long period of time — usually 30 years or more. One way to think about it is this: you pick your clothes to suit that day’s weather, but you have a range of clothes in your wardrobe that are suitable for the climate you live in.

10. Finally it's the battle of Celsius versus Centigrade. The temperature scale was originally developed by Anders Celsius and improved on by Jean Pierre Cristin, who called it the Centigrade scale, because it was divided into 100 degrees between the freezing and boiling points of water. But in 1948 the scale was officially renamed Celsius in honour of Anders. So drag yourself into the modern ways and use Celsius! (We’re not even going to talk about Fahrenheit and why the media switch to that during the summer…)

Of course, meteorological definitions can change with time, some fairly recent terms are still being discussed by scientists, such as meteotsunamis (a tsunami-like wave generated by meteorological factors rather than seismic activity) and medicanes (a portmanteau of Mediterranean and hurricane that refers to tropical cyclone-like storms that form in the Mediterranean Sea).