Tongan eruption sends atmospheric shockwaves around the world

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

The violent volcanic eruption in the Kingdom of Tonga on 15th January 2022 was so powerful it not only devastated the island nation; its impacts were felt around the world. A tsunami spread across the Pacific in a matter of hours, with waves hitting Australia, New Zealand and Japan, as well as the west coasts of North and South America. People as far away as Alaska and Canada heard the sonic boom, and barometers around the world recorded pressure changes from atmospheric shockwaves that rippled around the globe.

This is probably the best capture of the #Tonga #eruption shockwave I've seen yet. Imaged by the GOES-17 satellite in the infrared range. pic.twitter.com/e5HuM7skzY

— Dr. Casey Burton (@DrCaseyBurton) January 19, 2022

Tonga Volcano eruption heard from Lakeba, Fiji 😢🇹🇴 #TongaVolcano pic.twitter.com/qc9ISL25QX

— Portia Dugu (@portiajessene) January 15, 2022

Part of the Pacific “Ring of Fire”, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is a submarine volcano nearly 2 km high, with only its top 100 metres poking out of the sea. It has erupted regularly over the past few decades, with small eruptions over recent weeks. But the blast on 15th January was extremely violent, generating a pressure wave that blasted through the atmosphere at more than 1000 km/h. The amount of lightning strikes above the volcano increased dramatically a day or two before the cataclysmic eruption itself sparked almost 400,000 lightning bolts.

This is the most incredible #lightning loop that I have ever put together. #HongaTongaHungaHaapai #HungaTonga #Volcano eruption today with nearly 400k lightning events in just a few hours! pic.twitter.com/xqW70NLeVd

— Chris Vagasky (@COweatherman) January 15, 2022

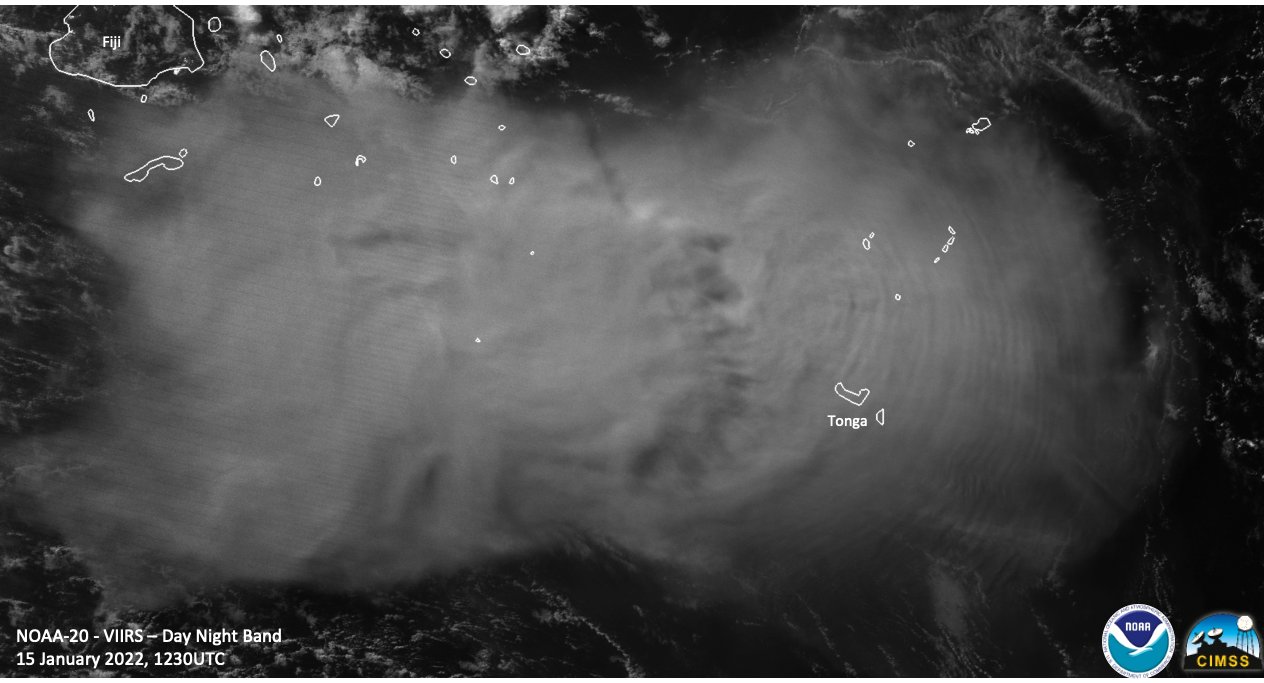

The volcanic eruption created a colossal mushroom cloud of ash, steam and gas that reached up to 30 km high, roughly three times the altitude at which commercial aircraft fly. Preliminary data from the University of Oxford suggests the volcanic cloud may even have reached an altitude of 39 km (128,000 ft).

A final video of today's explosive #Tonga #eruption.

— Simon Proud (@simon_sat) January 15, 2022

This shows data from all three weather satellites covering the area. From left to right: Korea's GK-2A, Japan's Himawari-8 and the US GOES-17.

Fascinating to see the different perspectives. pic.twitter.com/aB02QaayWx

Thunderstorm clouds flatten out at the tropopause, or top of the troposphere, since a lid of warm air suppresses their upward development. However, the plume of ash was so buoyant it was able to penetrate this layer and reach into the stratosphere. The ash cloud radiated out to a massive 260 km in diameter before being distorted by the wind and sweeping more than 3000 km west to Australia. Satellite imagery captured atmospheric gravity waves rippling outward from where the plume punctured the tropopause. A gravity wave is simply a wave moving through a stable layer of the atmosphere.

Absolutely mesmerizing view of "gravity waves" propagating along the "tropopause," or effective ceiling of the lower atmosphere, following the eruption of #HungaTonga this morning.

— Matthew Cappucci (@MatthewCappucci) January 15, 2022

The waves result from the plume's buoyancy bumping against the tropopause and causing ripples. pic.twitter.com/Tz5uyyhQqe

Twenty minutes after the eruption, tsunami waves up to 15 metres high hit the islands of Tonga, including the main island of Tongatapu. Less than an hour later, the volcano was raining ash and tiny pebbles on the Polynesian archipelago, coating everything with a layer of fine ash resembling grey snow. It took less than 5 hours for smaller tsunami waves to reach New Zealand and about 10 hours to reach Alaska.

🔴BREAKING NEWS!: 🌊 A major #tsunami (greater than 1.5 meters, according to our analyses) has been recorded in #Tonga, due to a significant eruption of the #HungaTongaHungaHaapai volcano 🌋.

— American Earthquakes 🌋🌊🌎 (@earthquakevt) January 15, 2022

Stay safe!.

Video: @sakakimoana.#EQVT,#erupción,#eruption,#eruzione,#Volcán,#Volcano. pic.twitter.com/7zpGqNPSN4

— Consulate of the Kingdom of Tonga (@ConsulateKoT) January 19, 2022

Meanwhile, the shockwave was traveling almost as fast as the speed of sound and causing noticeable jumps in atmospheric pressure as it reached the UK on the opposite side of the world about 15 hours after the eruption. Numerous weather stations recorded astonishing 2 to 3 millibar pressure changes during the passage of several waves. Shockwaves are formed when a pressure front moves at supersonic speeds and pushes on the surrounding air, usually heard as a loud crack or snap noise. During a shockwave, air pressure increases more than usual, as a result of the air being quickly compressed, and then decreases again.

Our atmosphere acts as a fluid, like dropping a pebble in a still pond and seeing the ripples.

— Met Office (@metoffice) January 16, 2022

A UK pressure trace for the past 24 hours shows how our atmosphere continues to see those ripples since the first pressure wave from the #Tonga eruption arrived on Saturday evening. pic.twitter.com/rr0xBONe4v

Shockwave from Hunga Tonga-Hunga Haʻapai eruption plume, seen by pressure change at UK sites. Wave moves southward down the country 18-20Z 15Jan. The same wave, but travelling the other way around the globe, moves northward up the country 01-03Z 16Jan. @RoostWeather @Silkstiniho pic.twitter.com/2jXaWwyzih

— Will Thurston (@imthursty) January 16, 2022

Another view of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai eruption shockwave from home weather stations across the UK. Initial wave propagates southwards Saturday evening, followed by the same wave (having travelled around the other side of the world) propagating northwards early Sunday 📉 pic.twitter.com/eaxOBeNlSx

— Dan Holley (@danholley_) January 16, 2022

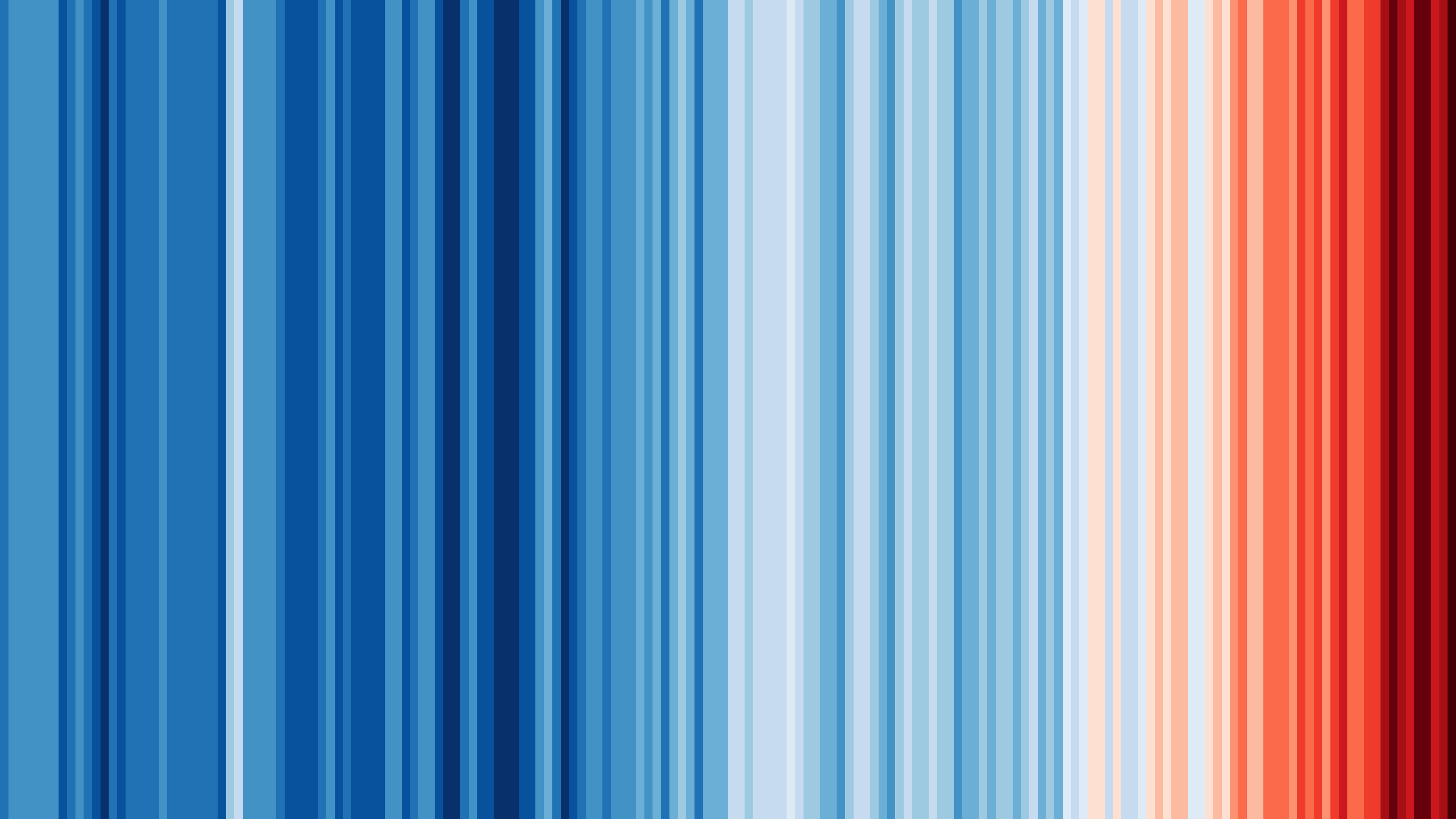

Volcanic eruptions can release enormous amounts of sulphur dioxide and other aerosols, which can produce a measurable cooling effect on the Earth’s climate by reflecting incoming sunlight. But initial data suggests the amount of sulphur dioxide the Tongan eruption blasted into the air was about 2 per cent of the amount produced by the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991. This means the eruption is unlikely to lower global temperatures. And it’s worth noting that the Pinatubo aerosols only had a short-term impact of a year or two, so the Tongan eruption is not going to buy us time in our battle against climate change.

However, the plume has already spread over Australia, with extremely high concentrations of sulphur dioxide above the Pacific Ocean and some becoming wrapped into cyclone Cody, east of New Zealand. Sulphur dioxide is potentially harmful to human health, worsening conditions such as asthma and causing acid rains.

The highest concentration of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the world right now is over the Pacific 📈

— NIWA Weather (@NiwaWeather) January 17, 2022

This is associated with the eruption of the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano 🌋

🧵 on what this means... pic.twitter.com/yjgT0yWdL8

1/ While we wait for more information from #Tonga following the eruption, our remote sensing scientists are keeping an eye on satellite data. This image shows the distribution of Sulphur Dioxide (which can cause local acid rain) from the volcano over the Pacific Ocean. pic.twitter.com/11s4Ro4RoH

— RAL Space (@RAL_Space_STFC) January 17, 2022

More pressing is the impact of the volcanic ash on water supplies on the Tongan archipelago and getting aid to the islands. So far, the ash cloud has hampered aid efforts, and there is also concern over aid workers bringing the Covid-19 virus. Meanwhile, communications with the Kingdom of Tonga have been severely disrupted making it difficult to assess the scale of the devastation.

.@UNOSAT produced a preliminary assessment of the impact from #HungaTongaHungaHaapai volcano: https://t.co/hZ4vheqRwg

— Disasters Charter (@DisastersChart) January 17, 2022

See a few extracts from the report, providing before and after comparisons using #Pleiades, #Sentinel2 and WorldView imagery. #TongaVolcano pic.twitter.com/XgzgPFycC3

Scientists are now starting to take the measure of the monster volcanic eruption that rocked the South Pacific kingdom of Tonga and made our atmosphere ring like a bell, albeit at a frequency too low for us to hear. A recent NASA assessment found that the Tonga volcanic eruption was one hundred times more powerful than the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. As for the height of the ash cloud, it would appear it reached even higher into our atmospher than first thought. In other words, the ash plume entered three layers of our atmosphere: the troposphere, the stratosphere and the mesosphere.

We've been looking into the Tonga eruption in more detail. Our latest data says that the main volcanic 'umbrella' reached 35km altitude - but some points (such as the image below) may have reached 55km altitude!

— Simon Proud (@simon_sat) January 20, 2022

Shocking altitudes that show just how violent this eruption was. https://t.co/AaL4td8MIb pic.twitter.com/55Im0Yvcub