Weather Photographer of the Year: Setting the scene - At dusk and dawn

Header image credit: Bijelic_Leon

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

Ever heard of the golden or magic hour? This is the hour or so after the sun rises, or the hour before the sun sets, when the sun’s rays are warm and golden. This magical light makes for some beautiful photographs, as can be seen in some of our favourite sunrise and sunset submissions to Weather Photographer of the Year.

True Colour

But why does the sky take on glorious hues of yellow, orange and red at dusk and dawn? It’s all thanks to a combination of factors; the colours in sunlight, the angle at which the sun’s rays travel through our atmosphere, the size of atmospheric molecules and particles, and also the way our eyes perceive colour.

While sunlight or visible light may appear white, it’s actually made up of a spectrum of different colours (remember those prism experiments at school that split light up into a rainbow of colours?). Light travels through space in a straight line as long as nothing disturbs it. In our atmosphere that can happen when light bumps into a gas molecule, mostly nitrogen and oxygen. What happens next depends on the wavelength of light.

Mr Blue Sky

Most of the longer wavelengths, the reds and oranges, will pass straight through. But the shorter wavelengths, the violets and blues, get absorbed by tiny gas molecules. The absorbed blue light is then radiated in different directions and scattered all around the sky, a process known as Rayleigh scattering.

Whichever direction you look, some of this scattered blue light reaches you. Since you see the blue light from everywhere overhead, the sky looks blue. In case you’re wondering why the sky isn’t purple, that’s down to biology and the fact our eyes, specifically the cones or colour receptors in our retina, are more sensitive to blue than violet.

Sandy sunsets

But at sunrise and sunset, the sun is very low in the sky, so the sunlight we see has travelled through a much thicker amount of atmosphere. This increased distance causes more of the blue portion of the sun’s rays to scatter away from our eyes, leaving relatively more of the yellow, orange and red light for us to see.

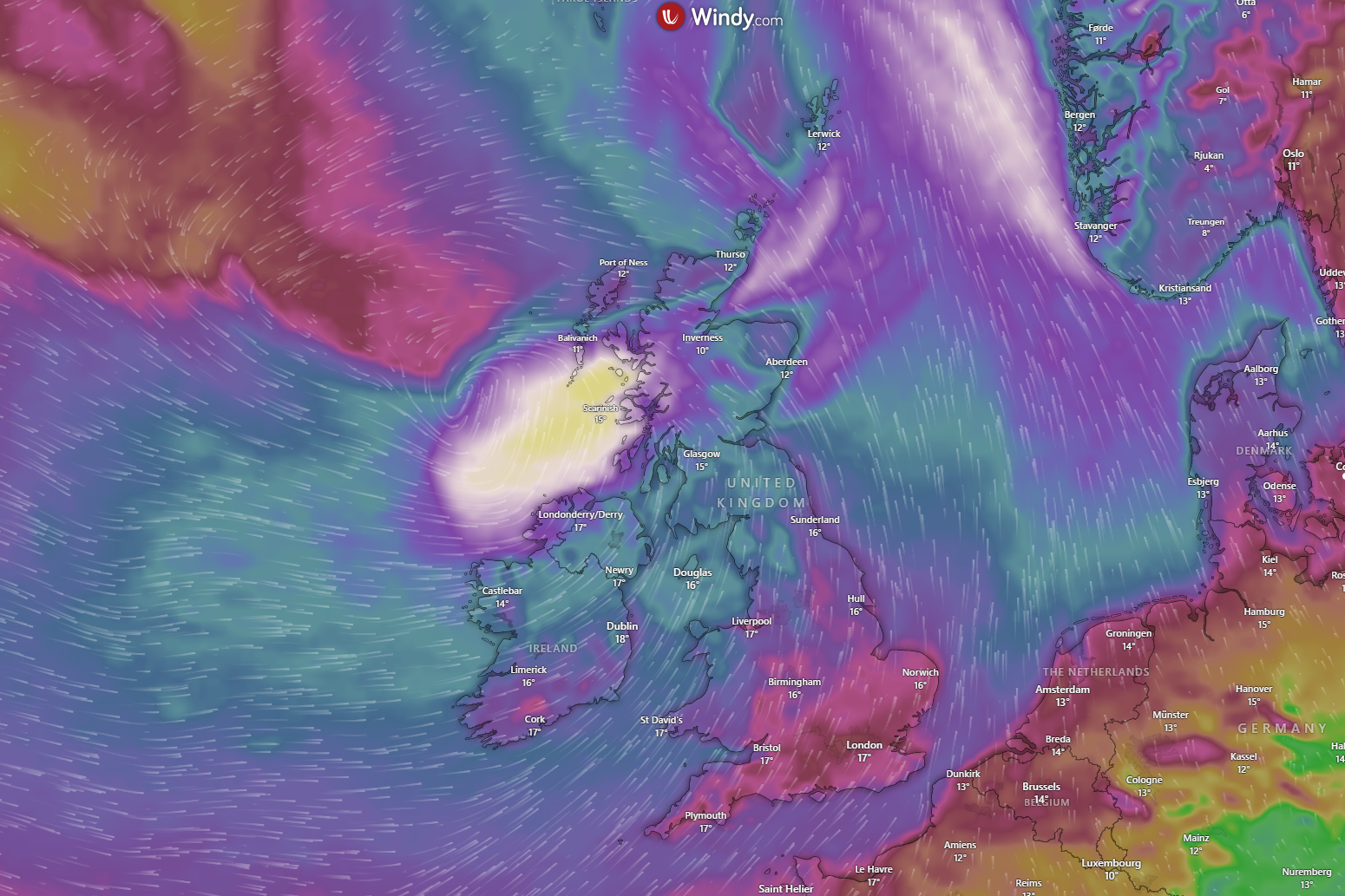

As well as gas molecules, our atmosphere also contains many small solid particles, like dust, soot, ash, pollen and salt. If the air is polluted with small particles, natural or otherwise, our sunsets become more red and vivid in colour. Many dramatic sunsets are thanks to dust particles courtesy of a Saharan sandstorm and a southerly air flow (see image above). Sunsets over the sea may also be orange due to the salt particles in the air.

Red Sky at Night

You’ve probably heard the expression, “Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Red sky in morning, shepherd’s warning”. Unlike other weather lore, this saying often holds true in the UK as our weather systems typically move west to east.

A red sky appears when dust and other small particles are trapped in the atmosphere by high pressure, scattering away most of the blue light. At sunset this means high pressure is moving in from the west, so the next day will be dry and pleasant. At sunrise, it means the high pressure system has already moved east, so the good weather has passed and more likely than not, a wet and windy low pressure system is heading our way.

An approaching weather front is another reason the sky may glow red in the morning. As the sun rises at a low angle in the east, it may light up the impending rain clouds coming in from the west. Likewise, red clouds in the evening will be those in the east that have already passed us by, giving a good chance of clear skies and fine weather ahead.

Start of summer

The magic of sunrise takes on extra significance during the summer solstice (which occurs between the 20th and 22nd of June in the northern hemisphere). This date marks the beginning of the astronomical summer and has been celebrated since ancient times as the longest day of the year. In a modern twist, the summer solstice sunrise at the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge is now live streamed.

But why isn’t the longest day of the year also the hottest day of the year? Just as a pan of water doesn’t start boiling the second you put it on a flame, it takes time for the atmosphere to heat up. The days may be at their longest, but it takes a couple of months for our atmosphere, land and seas to warm up, so we tend to get our highest temperatures in July and August. Which is why the summer solstice marks the beginning and not the peak of summer warmth.

Green flash

Finally, if you are out taking photographs in the golden hour, you might be lucky enough to spot the legendary green flash. This brief flash of green light lasts for no more than a few seconds shortly after sunset or just before sunrise.

It happens when the sun is almost entirely below the horizon, with the barest edge still visible. When the conditions are right, a distinct green spot is briefly visible above the upper rim of the sun’s disc. Even more rarely the green flash can resemble a green ray shooting up from the sunset or sunrise point.