Heatwaves

by Kirsty McCabe, FRMetS

What is a heatwave?

A heatwave is a prolonged period of abnormally high temperatures, relative to the expected conditions at that given time and place. The exact definition varies around the world, but all heatwaves are classed as extreme weather events.

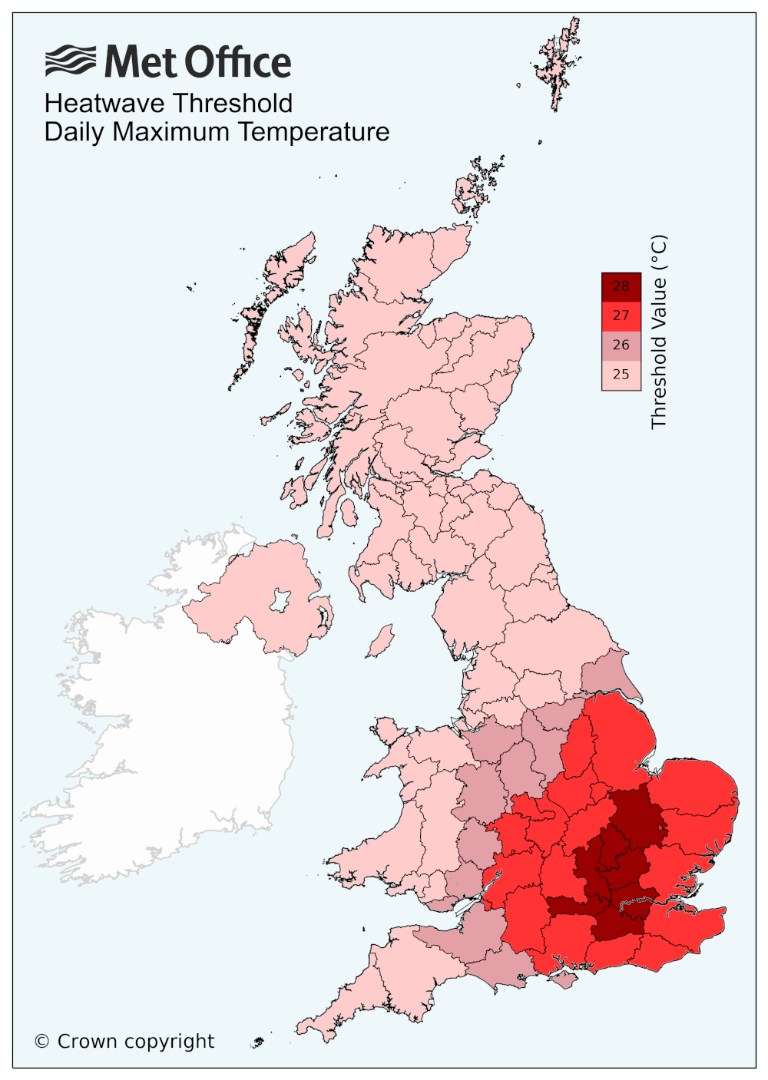

In the UK, the Met Office has defined a heatwave temperature threshold for each county – if the daily maximum temperature meets or exceeds this value for at least three consecutive days, it is classed as a heatwave. The figure below shows the threshold values for each county, ranging from 25°C to 28°C (updated in 2022).

Heatwaves are often caused by slow moving, high pressure systems in the UK. During the summer, the polar front and jet stream are usually found north of the UK, allowing high pressure to build in from the south. The high can persist for days or weeks, in which case it is referred to as a ‘blocking high’, as its presence prevents other weather systems from moving across the area and results in extended dry and settled weather.

Forecasters can identify the weather patterns that may result in a heatwave several days in advance, making them a little easier to predict than unsettled weather. At the start of June 2021, the Met Office launched a new Extreme Heat National Severe Weather Warning. These extreme heat warnings will be issued based on the impacts of the hot weather conditions, rather than when specific temperatures are reached.

This means that different conditions in different areas of the country may trigger an extreme heat warning, and the threshold for an extreme heat warning in Aberdeen, for example, is likely to be lower than one covering London. Amber and red warnings will inform the public of potential widespread disruption and adverse health effects.

Heatwaves and Health

Our core body temperature of 37°C is maintained by our metabolism. The body defends itself from heat through three mechanisms: relaxing hair muscles, sweating, and changing the blood flow. When we are hot, our hearts work hard to pump extra blood to the skin, which increases skin temperature and allows the body to radiate some heat. For the elderly, or anyone with chronic health problems, this can be enough to bring on a cardiac event.

Sweating also helps the body to cool off, but only when the humidity levels are low enough to allow the sweat to evaporate. The rate of evaporation depends on complex interactions between the air temperature, humidity and the wind. Dehydration, certain medications, tight clothing, lack of wind and high humidity are all factors that can impair the sweating process. At 27°C or above, people with compromised sweating mechanisms struggle to keep cool.

Certain groups are more at-risk from excessive heat during heatwaves. The elderly are less able to regulate their internal body temperature (called thermoregulation), while young children are more prone to dehydration and are not able to sweat as much. Individuals with chronic or severe illnesses are also at risk, particularly those with respiratory or cardiovascular diseases.

According to Public Health England (PHE), temperatures above 25°C are increasingly associated with excess summer deaths. To see this in action, we only have to look back a couple of years – the heatwaves that took place during summer 2019 resulted in almost 900 extra deaths across England. And during the heatwaves of summer 2020, there were 2,256 excess deaths across the country, the highest since records began. Other research into heatwaves has demonstrated the role of high night-time temperatures and how several days of exposure increases the probability of death, particularly for the elderly.

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke are well known heat-related illnesses, but others include heat cramps, heat rash, heat oedema (swelling) and heat syncope (fainting or dizziness). For more information, you can read Public Health England’s Making the case: the impact of heat on health – now and in the future.

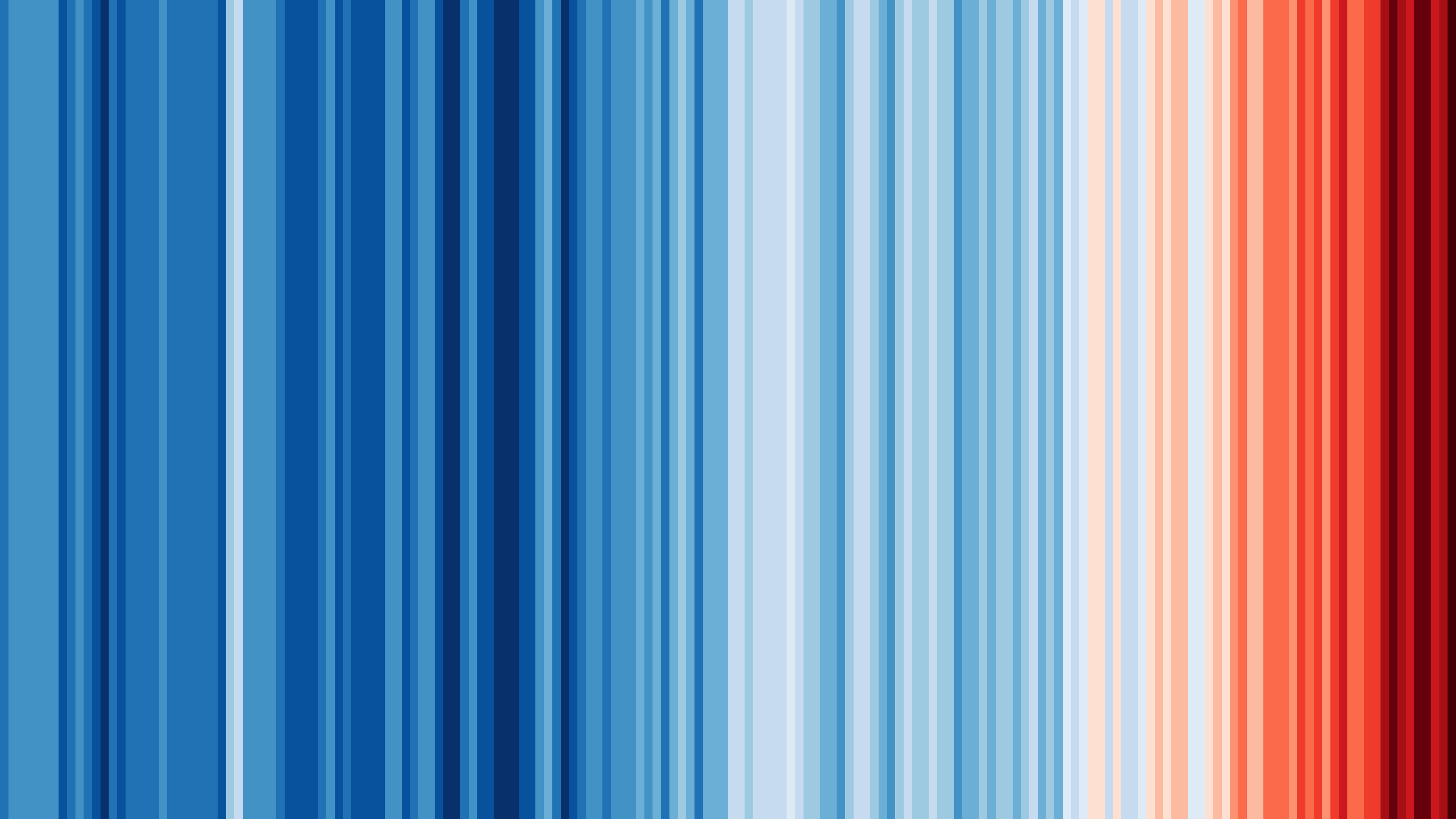

Heatwaves and Climate Change

Blaming a single heatwave event on global warming is complicated. However, it is possible to say that such extreme events are likely to happen more often, are hotter and are lasting longer due to human-induced climate change.

Indeed, the five hottest European summers since 1500 have all occurred this century, and the UK State of the Climate report shows that warm spells are lasting twice as long as they did 50 years ago (from 5.3 days in 1961-1990 to over 13 days in 2008-2017). In addition, extreme summer temperatures are now 30 times more likely than in pre-industrial times, and the average hottest day of the year has increased by 0.8°C above the 1961-1990 average.

For the first time ever, the UK recorded a maximum temperature of over 40 ºC in 2022, with 40.3 ºC recorded at Coningsby in Lincolnshire on 19th July.