Snowmakers in the UK - part 2

I have looked at one cause of major snowfall over the UK, the warm occlusion.

In this article I will look at the second trigger of significant snowfall, the Polar Low. Before I get on to those, let’s recap some winter air masses.

Over the UK, Polar maritime air masses are very common with winds that come from the north and west. This air starts off over the Greenland/Arctic Ocean and moves fairly slowly over a relatively warm sea surface, allowing the temperature and humidity to rise. By the time the air reaches us ‘wintry’ showers have developed and these run on to north and west-facing coasts. I like the term ‘wintry’ showers. It is an honest assessment of what can be forecast. In these circumstances, very small differences in temperature, altitude and humidity affect the type of precipitation. Rain, sleet (a mix of rain and snow), hail or snow can all fall from this air mass and it is tricky (…nigh on impossible!) to predict what will fall at a particular location at a particular time. The term ‘wintry showers’ encompasses all these precipitation types.

The next level up from Polar maritime is Arctic maritime, sometimes described as Polar maritime on steroids! It forms over the Arctic Ocean and travels rapidly directly south crossing the warmer seas very quickly. The rapidity of its movement means that is still very cold when it reaches us.

The warm water of the Gulf Stream means that the sea surface temperature between Scotland and Norway is abnormally high for its latitude. Very cold air over a warm sea leads to the formation of heavy showers. These fall almost exclusively as snow and/or hail, even produce thunderstorms, otherwise known as ‘THUNDERSNOW’!

I concede it is a cool thing to see (or hear) but ‘thundersnow’ is actually a common phenomenon and not really worthy of the media frenzy it usually produces. The heavy snow showers rapidly die out as they move over the cold land and only affect a narrow coastal strip, a matter of a few kilometres inland. However, in those areas large accumulations are possible.

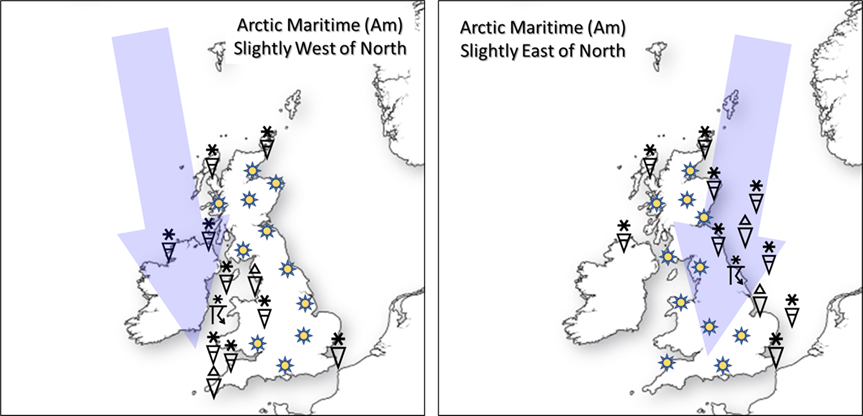

In forecasting, the key factor is the exact wind direction, it is this that controls the distribution of showers. Winds slightly east of north concentrate the showers on the east coast, slightly west and they are concentrated in the west.

In the east, the distribution pattern is very relatively straightforward. The coast is ‘smooth’. In the west, the coast is more complicated and produces areas where the showers become more concentrated. A line of showers often develops off the end of Pembrokeshire, ‘hanging’ southwards over Devon and Cornwall, also known as the Pembrokeshire Dangler. This can produce large snowfalls over Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor.

An Arctic maritime air mass can produce significant snowfall itself, but only in a very narrow coastal strip. A Polar low extends this risk much further inland. But these are not just lows that come from the pole, in fact, a Polar low is a very specific mesoscale weather system.

Mesoscale? Well, ‘normal’ areas of low pressure are thought of as being ‘broadscale’ features, in other words they developed due to changes in the atmosphere on a global and/or continental scale. A mesoscale feature is one that is mainly driven by interactions between the surface and lower atmosphere, and/or smaller structures that run around broadscale features. They are on a ‘meso’ or ‘mid’ scale. Tropical storms are also mesoscale features so do not confuse size with power or impact!!

‘Normal’ Arctic maritime showers are driven by convection over the relatively warm sea. In a Polar low, there is an extra trigger. This is usually a small feature, a ripple in the upper atmospheric flow referred to as a trough. As the trough approaches, the air ahead of it tends to diverge at the top of the atmosphere. The reasons for this are beyond the scope of this article, but on a large scale the process gives rise to large Atlantic storms. On the small scale, it slightly reduces surface pressure, producing a Polar low. Air spirals in at the bottom and out at the top. The combination of air being ‘pushed’ up by convection and ‘sucked’ up in the Polar low allows showers and thunderstorms to penetrate inland.

On the east coast, the flat land over Lincolnshire and East Anglia makes for easy and rapid passage toward the fragile transport systems of London and the southeast. 31st January 2003 was known as ‘White Friday’. Temperatures were not especially low but small troughs and Polar lows brought heavy snow to eastern England. The A1 was blocked in many places but it was the M11 that made most of the headlines with drivers stuck for over twenty-four hours by snow, ice and lorries.

Polar lows in the west have a harder time. The coast is more complex with high ground close to the coast. Areas of west Wales and southwest England are most at risk.

Polar lows do not look particularly scary on a pressure chart. They are not the big Atlantic ‘dartboards’ that we associate with bad weather, but they punch well above their weight. If you see a strong northerly flow on a chart in mid-winter watch out for small innocent looking ripples in the flow. If you are in the wrong place at the wrong time, they can make life very difficult.

About the author

Frank Barrow retired from the Met Office in 2020, after a career of 39 years during which he worked as an observer in the 1980s, a forecaster in the 90s and, since 1996, as a trainer at the Met Office College. He describes the latter role as “fitting him like a glove”, so he stayed... for almost 25 years! During that time, he was involved in the training of the vast majority of current Met Office forecasters.